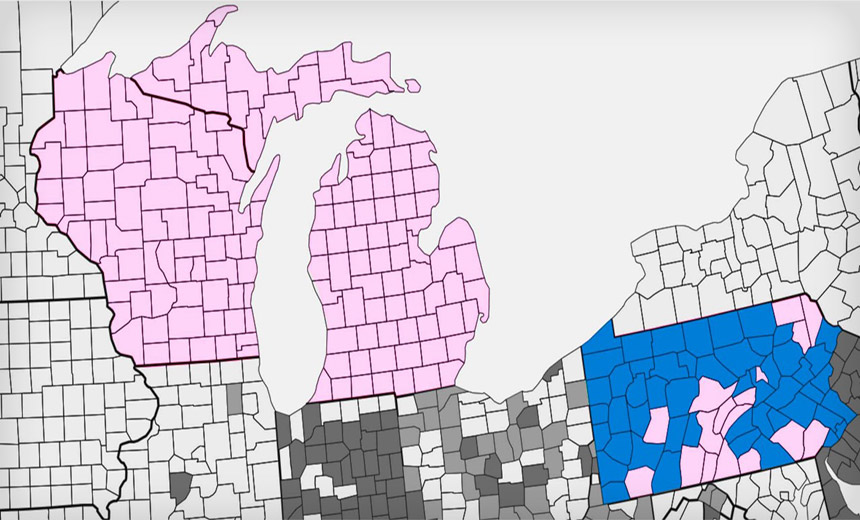

Counties that use paperless voting machines (blue) require digital forensic analysis to verify results, unlike optical scan paper ballots (pink). Source: Medium

Counties that use paperless voting machines (blue) require digital forensic analysis to verify results, unlike optical scan paper ballots (pink). Source: MediumA group composed of computer scientists and activists has proposed that U.S. election results be audited in three key states in which President-elect Donald Trump won by a razor-thin margin. The group's goal is to definitively disprove that hackers may have influenced the contentious election.

See Also: How to Identify and Mitigate Threats on Your Network by Using a CASB

The group's fears are rooted in the gross inaccuracy of pre-election polls, which almost universally predicted a victory by Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. The campaign was also marred by data leaks allegedly perpetrated by Russians in an apparent attempt to influence election results, during what many commentators characterized as one of the most bitter and unconventional elections in memory (see Did Russia - or Russian-Built Malware - Hack the DNC?).

Backing for the election-results auditing comes in part via Ron Rivest, a cryptographer who in part developed the RSA algorithm, as well as Philip Stark, an associate dean of mathematical and physical sciences at the University of California. They co-authored an editorial published Nov. 18 in USA Today calling for election results to be audited by default.

Further support for suchg an effort comes via J. Alex Halderman, a professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan, who has done extensive research into the security vulnerabilities of electronic voting machines.

When it comes to detailing their reasons for wanting an audit, the academics appear to be erring on the side of caution, and noting that they have not seen any evidence of direct hacker interference.

"Were this year's deviations from pre-election polls the results of a cyber attack? Probably not," Halderman writes in a post on Medium. "I believe the most likely explanation is that the polls were systematically wrong, rather than that the election was hacked."

New York Magazine reported that Clinton performed worse in counties in Wisconsin that used electronic voting machines rather than those that use paper ballots, which are counted by optical scanners. Halderman has disputed the accuracy of the article, but other analysts have tried to see if it might reveal an anomaly with hacking implications.

FiveThirtyEight, the statistical analysis service owned by ESPN, says it so far hasn't found clear evidence that the type of voting system in a particular state or county affected the outcome. The seeming disparity in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin disappears when adjusted for voters' race and education, writes Nate Silver, FiveThirtyEight's editor in chief.

...the effect COMPLETELY DISAPPEARS once you control for race and education levels, the key factors in predicting vote shifts this year. pic.twitter.com/NYOINx9lEz

"Maybe a more complicated analysis would reveal something, but usually [it's] bad news when a finding can't survive a basic sanity check like this," he writes on Twitter.

A Clinton Challenge?

Hillary Clinton's window to challenge the election results is rapidly closing. Halderman writes that deadlines to file recount petitions are Nov. 25 in Wisconsin, Nov. 28 in Pennsylvania and Dec. 1 in Michigan, which hasn't finished counting its votes.

Computers counted nearly all of the 129 million votes cast in the election. Some states would be easier than others to recount. Michigan and Wisconsin predominantly use paper ballots that are counted by optical scanners. An audit there would mean verifying that the optical scanners return the accurate result as selected by voters.

Pennsylvania, though, is problematic. Less than one-third of the state's counties use paper ballots counted by optical scanners. The rest have direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting machines, which experts have long warned are troublesome because they generate no paper record that can be audited. Many states, such as Nevada and California, have mandated that DRE machines also generate a paper record or receipt.

An audit of paperless DRE machines would thus require extensive testing of machines. If evidence emerged that malicious software may have tampered with vote results, a digital forensic analysis might then be the only way to verify the integrity - or lack thereof - of the machines.

The computer scientists contend that a full recount in particular states wouldn't be needed, at least at first. Instead, they say that a risk-limiting audit, which relies on a small sampling, could be used. If that audit turned up any irregularities, then a broader audit could be conducted.

Voting machines typically aren't connected to the internet, which limits hackers' options. But Halderman writes that the procedures for loading voting machines with ballot selections is ripe for abuse.

Ballot designs are copied from a regular desktop computer and loaded onto a removable drive, he writes.

"That initial computer is almost certainly not well secured, and if an attacker infects it, vote-stealing malware can hitch a ride to every voting machine in the area," Halderman writes. "There's no question that this is possible for technically sophisticated attackers."

Looking Ahead

Even if the buzz around the audit idea fizzles, it may help publicize longstanding concerns over the voting security, says Pamela Smith, president of Verified Voting, which is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization.

Election results should be audited even absent concerns of irregularities, she says. Verified Voting has launched a petition supporting a risk-limited audit of the presidential election.

"I think it's helping having this be on everyone's mind," Smith says. "At the end of the day, whether you voted for the losing candidate or the winning candidate, there's something very satisfying about being able to say, 'And we checked and it was what it was.' It helps erase any lingering doubt."