Endpoint Security , Risk Management , Technology

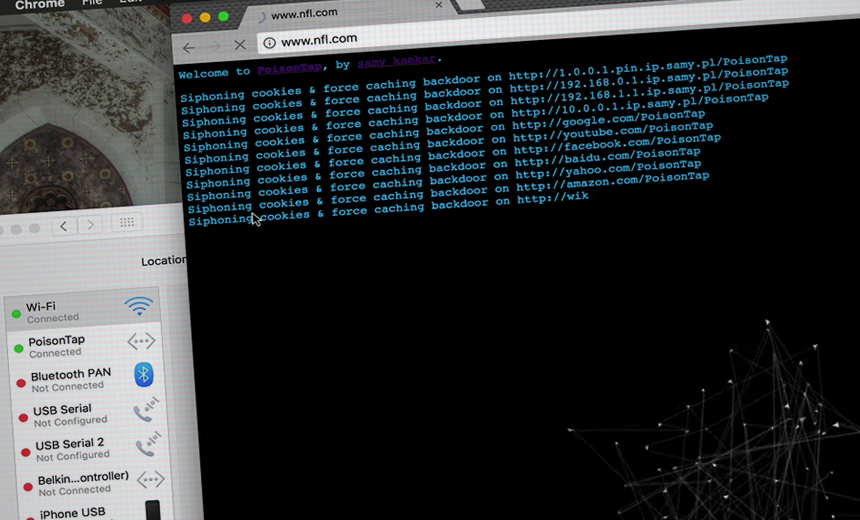

Locked PCs No Match for Samy Kamkar's Latest Hacking Tool PoisonTap Sneaks Into Computers, Even If They're Locked Image from Samy Kamkar video on PoisonTap

Image from Samy Kamkar video on PoisonTapIt's an innocent act: Close the lid on the laptop and go for a burrito at lunch. The laptop locks itself and goes into a mid-day snooze. But as prolific hacker Samy Kamkar shows with his latest experiment, this feeling of security is an illusion.

See Also: Faster Payments, Faster Fraud?

Kamkar, who most famously created the MySpace worm a decade ago, pushes the bounds of hacking possibilities, finding creative ways to disrupt systems. And his most recent work, which he calls PoisonTap, is yet another illustration of how tradeoffs made between security and convenience can open up dangerous security holes.

Kamkar built PoisonTap using a $5 Raspberry Pi Zero computer, a microUSB cable and a microSD card. Although physical access to a computer is required to insert the device, from there it doesn't rely on any software vulnerabilities to accomplish its misdeeds. Instead, it takes advantage of the implicit trust put in connected devices and produces "a snowball effect of information exfiltration, network access and installation of semi-permanent backdoors," Kamkar writes on his blog.

Kamkar has released the source code for PoisonTap on GitHub along with a demonstration video.

Locked, But Not Really Locked

When computers go into a locked state, most users would think nothing gets in or out. But Kamkar found that even if a computer requires a password to gain access again, he could skip over that step by inserting his malicious USB device.

When the computer then asks PoisonTap for an IP address, it impersonates an ethernet device. And rather than just responding as a local network device, PoisonTap pretends it's the entire internet IPv4 address space. The computer then prioritizes PoisonTap's connection because it's a local area network and subsequently routes all of its internet traffic over it.

The trouble starts there, and Kamkar found all kinds of ways to tamper with a computer even if PoisonTap is physically connected to a computer for only a short period. He found he could easily steal certain types of cookies, which are small data files stored within a web browser that allow, for example, visitors to continue to access a website without logging in again.

By spoofing DNS requests, Kamkar could deliver hidden iframes to a person's web browser that impersonated popular websites and then collect those sites' cookies. It should be noted that this attack will not work if websites are encrypted, designated by "https" in the URL window, or if cookies have been flagged with the "secure" setting.

The implanted iframes, though, don't disappear - even if PoisonTap is removed. The browser caches them, which makes them essentially backdoors unless someone flushes their browser's cache, which regular users rarely do. The backdoor could also allow an attacker to have access to the user's router, Kamar writes.

"This can lead to other attacks on the router which the attacker may have never had access to in the first place, such as default admin credentials on the router being used to overwrite DNS servers or other authentication vulnerabilities being exposed," he writes.

The Glue Defense

The sure-fire defense against PoisonTap is one that has been used for a long time: permanently plugging USB ports with epoxy.

As noted before, PoisonTap is also ineffective if websites are encrypted. Following the leaks from former National Security Agecy contractor Edward Snowden that revealed large-scale government spying operations, more and more websites are implementing encryption, but the massive effort is far from complete.

Closing web browsers when leaving a computer unattended is another defense, although Kamkar notes that behavior "is entirely impractical."

There are also some platform-specific tips: Enabling FileVault, macOS's full-disk encryption feature, is recommended. When Macs go into a deep sleep, "your browser will no longer make requests, even if woken up," Kamkar writes.

Even though macOS has a setting that requires an administrator password before a change to network setting is allowed, Kamkar wrote on Twitter that "it only prevents *manual* network changes, yet still auto-provisions new devices."