Anti-Malware , DDoS , DDoS Attacks

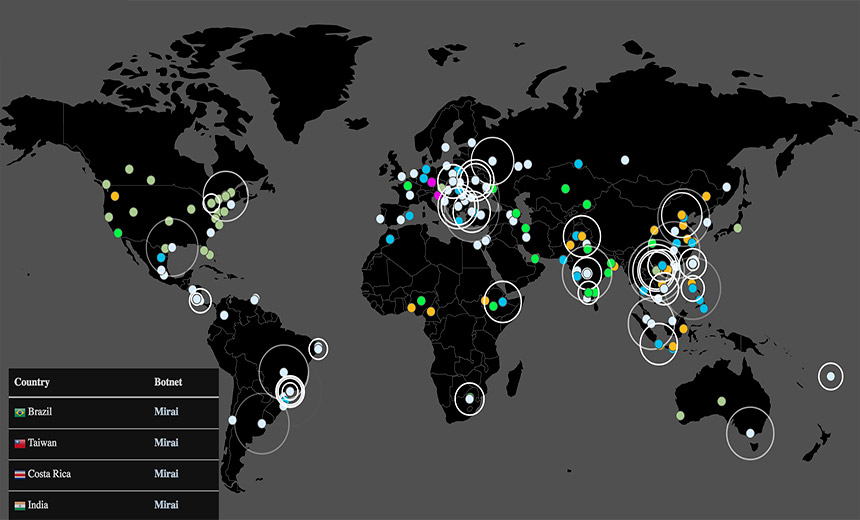

Mirai Malware Is Still Launching DDoS Attacks But Code Flaws and Attack Track-Backs Could Help Battle IoT Botnets Mirai botnet tracker via MalwareTech.

Mirai botnet tracker via MalwareTech.We were promised flying cars. Instead, we get malware-infected surveillance cameras serving as remote launch pads for digital attacks that help criminals earn cryptocurrency by disrupting large parts of our global computer network.

See Also: Main Cyber Attack Destinations in 2016

The Oct. 21 IoT botnet attacks against domain name server provider Dyn, largely driven by Mirai malware, resulted in intermittent disruptions for internet users attempting to access many major sites, including Amazon, GitHub, Reddit, SoundCloud, Spotify, Tumblr and Twitter.

But that wasn't the end of DNS-targeting distributed denial-of-service attacks launched by purloined IoT devices.

The next day, Singaporean ISP StarHub's DNS services were also attacked and disrupted. And that happened again on Oct. 24.

To date, the ISP hasn't divulged what type of malware was used to target it. In addition to Mirai, Bashlite is another likely culprit. It's also not clear whether attackers might directly control the botnet or if they coughed up some bitcoins to rent someone else's stresser/booter DDoS-on-demand service.

But StarHub CTO Mock Pak Lum did say that his company traced the attacks to malware-infected IoT devices owned by its home broadband subscribers. StarHub has so far declined to tell me which malware was used, or if any of the hacked devices had been issued by the ISP to its customers.

Whether or not Mirai malware targeted StarHub, attackers are continuing to use it, according to Peter Kruse, a partner and e-crime specialist working with CSIS Security Group in Denmark.

#Mirai DDoS targets observed with in the past 24 hours. pic.twitter.com/CkgdTqlYaO

"Mirai continues to be used in a string of DDoS attacks. It may not be in the headlines but it hasn't gone away," Alan Woodward, a University of Surrey computer science professor, warns via Twitter. "Just think of all that bandwidth being used up in what is effectively friction loss," he adds.

Mirai Diversifies

Following the release of the Mirai source code last month, Mirai botnet variants in the wild are being run by multiple groups, according to a blog post from Roland Dobbins and Steinthor Bjarnason, security engineers at DDoS defense firm Arbor Networks.

"The original Mirai botnet ... currently consists of a floating population of approximately 500,000 compromised IoT devices worldwide," they say.

Thankfully, some weaknesses in the internet of things attack landscape are already starting to appear.

Scott Tenaglia, a research director at security firm Invincea Labs, reports that in Mirai, there's "a stack buffer overflow vulnerability in the HTTP flood attack code," which can be exploited to "cause a segmentation fault (i.e. SIGSEV [segmentation violation]) to occur, crash the process, and therefore terminate the attack from that bot."

In other words, one of the leading types of IoT-device-infecting malware, Mirai, has a flaw that could be targeted to crash the attack code.

Tenaglia, in a blog post, stresses that he's sharing this finding for informational purposes only. "We are not advocating counterattack, but merely showing the possibility of using an active defense strategy to combat a new form of an old threat," he says (see Could a Defensive Hack Fix the Internet of Things?).

Unfortunately, targeting buffer overflow vulnerabilities wouldn't spell the end of IoT botnets. As ransomware developers have done, IoT malware developers would likely just improve their code to remove the bugs, then keep on attacking.

Tracing Attacks Back

Another potential defense against IoT-launched DDoS attacks might be to find better ways to separate attack traffic from legitimate traffic, so that the former can be blocked while the latter still flows. And one potential aid could be identifying attack packets' origins.

On that front, researchers at the Center for IT Security, Privacy, and Accountability - CISPA - in Germany report that they've developed a technique that can mix data collected via distributed honeypots with trilateration techniques, which look at the "time to live" field in packet headers to approximate where packets originated. "If attacks abuse many honeypots at the same time, the honeypots allow measuring the path lengths between the packet origin and the various honeypot placements," the researchers write in their paper, "Identifying the Scan and Attack Infrastructures Behind Amplification DDoS Attacks," which they presented this week in Vienna at the 23rd ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

Amplification attacks of the type experienced by Dyn typically begin with a scanner that conducts reconnaissance on the target, followed by attack nodes being directed against the target. The researchers, however, claim they found that their combination of techniques could be used to reliably identify the origin of DNS amplification attacks, including associated scanners, 58 percent of the time, as well as almost 100 percent of the attacking endpoints.

Tracing DDoS attacks back to their origin may give law enforcement agencies and ISPs greater impetus to at least quarantine offending devices. "We have shared our findings with law enforcement agencies - in particular, Europol and the FBI - and a closed circle of tier-1 network providers that use our insights on an operational basis," the researchers write. "Our output can be used as forensic evidence both in legal complaints and in ways to add social pressure against spoofing sources."

It's unclear if police or social pressure will help lock down hacked IoT devices. StarHub, meanwhile, tells me that it's now dispatching customer service teams to subscribers' residences to patch or otherwise deal with infected IoT devices.

Neither approach offers a full-fledged fix. But for mitigating attacks driven by botnets of IoT devices, every little bit might help.