WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Two weeks after leaving her position as an intelligence analyst for the U.S. National Security Agency in 2014, Lori Stroud was in the Middle East working as a hacker for an Arab monarchy.

She had joined Project Raven, a clandestine team that included more than a dozen former U.S. intelligence operatives recruited to help the United Arab Emirates engage in surveillance of other governments, militants and human rights activists critical of the monarchy.

Stroud and her team, working from a converted mansion in Abu Dhabi known internally as “the Villa,” would use methods learned from a decade in the U.S intelligence community to help the UAE hack into the phones and computers of its enemies.

Stroud had been recruited by a Maryland cyber security contractor to help the Emiratis launch hacking operations, and for three years, she thrived in the job. But in 2016, the Emiratis moved Project Raven to a UAE cyber security firm named DarkMatter. Before long, Stroud and other Americans involved in the effort say they saw the mission cross a red line: targeting fellow Americans for surveillance.

“I am working for a foreign intelligence agency who is targeting U.S. persons,” she told Reuters. “I am officially the bad kind of spy.”

The story of Project Raven reveals how former U.S. government hackers have employed state-of-the-art cyber-espionage tools on behalf of a foreign intelligence service that spies on human rights activists, journalists and political rivals.

Interviews with nine former Raven operatives, along with a review of thousands of pages of project documents and emails, show that surveillance techniques taught by the NSA were central to the UAE’s efforts to monitor opponents. The sources interviewed by Reuters were not Emirati citizens.

The operatives utilized an arsenal of cyber tools, including a cutting-edge espionage platform known as Karma, in which Raven operatives say they hacked into the iPhones of hundreds of activists, political leaders and suspected terrorists. Details of the Karma hack were described in a separate Reuters article today.

An NSA spokesman declined to comment on Raven. An Apple spokeswoman declined to comment. A spokeswoman for UAE’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined to comment. The UAE’s Embassy in Washington and a spokesman for its National Media Council did not respond to requests for comment.

The UAE has said it faces a real threat from violent extremist groups and that it is cooperating with the United States on counter-terrorism efforts. Former Raven operatives say the project helped NESA break up an ISIS network within the Emirates. When an ISIS-inspired militant stabbed to death a teacher in Abu Dhabi in 2014, the operatives say, Raven spearheaded the UAE effort to assess if other attacks were imminent.

Various reports have highlighted the ongoing cyber arms race in the Middle East, as the Emirates and other nations attempt to sweep up hacking weapons and personnel faster than their rivals. The Reuters investigation is the first to reveal the existence of Project Raven, providing a rare inside account of state hacking operations usually shrouded in secrecy and denials.

The Raven story also provides new insight into the role former American cyberspies play in foreign hacking operations. Within the U.S. intelligence community, leaving to work as an operative for another country is seen by some as a betrayal. “There’s a moral obligation if you’re a former intelligence officer from becoming effectively a mercenary for a foreign government,” said Bob Anderson, who served as executive assistant director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation until 2015.

While this activity raises ethical dilemmas, U.S. national security lawyers say the laws guiding what American intelligence contractors can do abroad are murky. Though it’s illegal to share classified information, there is no specific law that bars contractors from sharing more general spycraft knowhow, such as how to bait a target with a virus-laden email.

The rules, however, are clear on hacking U.S. networks or stealing the communications of Americans. “It would be very illegal,” said Rhea Siers, former NSA deputy assistant director for policy.

The hacking of Americans was a tightly held secret even within Raven, with those operations led by Emiratis instead. Stroud’s account of the targeting of Americans was confirmed by four other former operatives and in emails reviewed by Reuters.

The FBI is now investigating whether Raven’s American staff leaked classified U.S. surveillance techniques and if they illegally targeted American computer networks, according to former Raven employees interviewed by federal law enforcement agents. Stroud said she is cooperating with that investigation. No charges have been filed and it is possible none will emerge from the inquiry. An FBI spokeswoman declined to comment.

PURPLE BRIEFING, BLACK BRIEFING

Stroud is the only former Raven operative willing to be named in this story; eight others who described their experiences would do so only on condition of anonymity. She spent a decade at the NSA, first as a military service member from 2003 to 2009 and later as a contractor in the agency for the giant technology consultant Booz Allen Hamilton from 2009 to 2014. Her specialty was hunting for vulnerabilities in the computer systems of foreign governments, such as China, and analyzing what data should be stolen.

In 2013, her world changed. While stationed at NSA Hawaii, Stroud says, she made the fateful recommendation to bring a Dell technician already working in the building onto her team. That contractor was Edward Snowden.

“He’s former CIA, he’s local, he’s already cleared,” Stroud, 37, recalled. “He’s perfect!” Booz and the NSA would later approve Snowden’s transfer, providing him with even greater access to classified material.

Two months after joining Stroud’s group, Snowden fled the United States and passed on thousands of pages of top secret program files to journalists, detailing the agency’s massive data collection programs. In the maelstrom that followed, Stroud said her Booz team was vilified for unwittingly enabling the largest security breach in agency history.

“Our brand was ruined,” she said of her team.

In the wake of the scandal, Marc Baier, a former colleague at NSA Hawaii, offered her the chance to work for a contractor in Abu Dhabi called CyberPoint. In May 2014, Stroud jumped at the opportunity and left Booz Allen.

CyberPoint, a small cyber security contractor headquartered in Baltimore, was founded by an entrepreneur named Karl Gumtow in 2009. Its clients have included the U.S. Department of Defense, and its UAE business has gained media attention.

In an interview, Gumtow said his company was not involved in any improper actions.

Stroud had already made the switch from government employee to Booz Allen contractor, essentially performing the same NSA job at higher pay. Taking a job with CyberPoint would fulfill a lifelong dream of deploying to the Middle East and doing so at a lucrative salary. Many analysts, like Stroud, were paid more than $200,000 a year, and some managers received salaries and compensation above $400,000.

She understood her new job would involve a counterterrorism mission in cooperation with the Emiratis, a close U.S. ally in the fight against ISIS, but little else. Baier and other Raven managers assured her the project was approved by the NSA, she said. With Baier’s impressive resume, including time in an elite NSA hacking unit known as Tailored Access Operations, the pledge was convincing. Baier did not respond to multiple phone calls, text messages, emails, and messages on social media.

In the highly secretive, compartmentalized world of intelligence contracting, it isn’t unusual for recruiters to keep the mission and client from potential hires until they sign non-disclosure documents and go through a briefing process.

When Stroud was brought into the Villa for the first time, in May 2014, Raven management gave her two separate briefings, back-to-back.

In the first, known internally as the “Purple briefing,” she said she was told Raven would pursue a purely defensive mission, protecting the government of the UAE from hackers and other threats. Right after the briefing ended, she said she was told she had just received a cover story.

She then received the “Black briefing,” a copy of which was reviewed by Reuters. Raven is “the offensive, operational division of NESA and will never be acknowledged to the general public,” the Black memo says. The NESA, or National Electronic Security Authority, was the UAE’s version of the NSA.

Stroud would be part of Raven’s analysis and target-development shop, tasked with helping the government profile its enemies online, hack them and collect data. Those targets were provided by the client, NESA, now called the Signals Intelligence Agency.

The language and secrecy of the briefings closely mirrored her experience at the NSA, Stroud said, giving her a level of comfort.

The information scooped up by Raven was feeding a security apparatus that has drawn international criticism. The Emirates, a wealthy federation of seven Arab sheikhdoms with a population of 9 million, is an ally of neighbor Saudi Arabia and rival of Iran.

Like those two regional powers, the UAE has been accused of suppressing free speech, detaining dissidents and other abuses by groups such as Human Rights Watch. The UAE says it is working closely with Washington to fight extremism “beyond the battlefield” and is promoting efforts to counter the “root causes” of radical violence.

Raven’s targets eventually would include militants in Yemen, foreign adversaries such as Iran, Qatar and Turkey, and individuals who criticized the monarchy, said Stroud and eight other former Raven operatives. Their accounts were confirmed by hundreds of Raven program documents reviewed by Reuters.

Under orders from the UAE government, former operatives said, Raven would monitor social media and target people who security forces felt had insulted the government.

“Some days it was hard to swallow, like [when you target] a 16-year-old kid on Twitter,” she said. “But it’s an intelligence mission, you are an intelligence operative. I never made it personal.”

The Americans identified vulnerabilities in selected targets, developed or procured software to carry out the intrusions and assisted in monitoring them, former Raven employees said. But an Emirati operative would usually press the button on an attack. This arrangement was intended to give the Americans “plausible deniability” about the nature of the work, said former Raven members.

TARGETING ‘GYRO’ AND ‘EGRET’

Stroud discovered that the program took aim not just at terrorists and foreign government agencies, but also dissidents and human rights activists. The Emiratis categorized them as national security targets.

Following the Arab Spring protests and the ousting of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, Emirati security forces viewed human rights advocates as a major threat to “national stability,” records and interviews show.

One of the program’s key targets in 2012 was Rori Donaghy, according to former Raven operatives and program documents. Donaghy, then 25, was a British journalist and activist who authored articles critical of the country’s human rights record. In 2012, he wrote an opinion piece for the Guardian criticizing the UAE government’s activist crackdown and warning that, if it continued, “those in power face an uncertain future.”

Before 2012, the former operatives said, the nascent UAE intelligence-gathering operation largely relied on Emirati agents breaking into the homes of targets while they were away and physically placing spyware on computers. But as the Americans built up Raven, the remote hacking of Donaghy offered the contractors a tantalizing win they could present to the client.

Because of sensitivity over human rights violations and press freedom in the West, the operation against a journalist-activist was a gamble. “The potential risk to the UAE Government and diplomatic relations with Western powers is great if the operation can be traced back to UAE,” 2012 program documents said.

To get close to Donaghy, a Raven operative should attempt to “ingratiate himself to the target by espousing similar beliefs,” the cyber-mercenaries wrote. Donaghy would be “unable to resist an overture of this nature,” they believed.

Posing as a single human rights activist, Raven operatives emailed Donaghy asking for his help to “bring hope to those who are long suffering,” the email message said.

The operative convinced Donaghy to download software he claimed would make messages “difficult to trace.” In reality, the malware allowed the Emiratis to continuously monitor Donaghy’s email account and Internet browsing. The surveillance against Donaghy, who was given the codename Gyro, continued under Stroud and remained a top priority for the Emirates for years, Stroud said.

Donaghy eventually became aware that his email had been hacked. In 2015, after receiving another suspicious email, he contacted a security researcher at Citizen Lab, a Canadian human rights and digital privacy group, who discovered hackers had been attempting for years to breach his computer.

Reached by phone in London, Donaghy, now a graduate student pursuing Arab studies, expressed surprise he was considered a top national security target for five years. Donaghy confirmed he was targeted using the techniques described in the documents.

“I’m glad my partner is sitting here as I talk on the phone because she wouldn’t believe it,” he said. Told the hackers were American mercenaries working for the UAE, Donaghy, a British citizen, expressed surprise and disgust. “It feels like a betrayal of the alliance we have,” he said.

Stroud said her background as an intelligence operative made her comfortable with human rights targets as long as they weren’t Americans. “We’re working on behalf of this country’s government, and they have specific intelligence objectives which differ from the U.S., and understandably so,” Stroud said. “You live with it.”

Prominent Emirati activist Ahmed Mansoor, given the code name Egret, was another target, former Raven operatives say. For years, Mansoor publicly criticized the country’s war in Yemen, treatment of migrant workers and detention of political opponents.

In September 2013, Raven presented senior NESA officials with material taken from Mansoor’s computer, boasting of the successful collection of evidence against him. It contained screenshots of emails in which Mansoor discussed an upcoming demonstration in front of the UAE’s Federal Supreme Court with family members of imprisoned dissidents.

FILE PHOTO: Edward Snowden speaks via video link during a news conference in New York , U.S., September 14, 2016. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid/File Photo

Raven told UAE security forces Mansoor had photographed a prisoner he visited in jail, against prison policy, “and then attempted to destroy the evidence on his computer,” said a Powerpoint presentation reviewed by Reuters.

Citizen Lab published research in 2016 showing that Mansoor and Donaghy were targeted by hackers — with researchers speculating that the UAE government was the most likely culprit. Concrete evidence of who was responsible, details on the use of American operatives, and first-hand accounts from the hacking team are reported here for the first time.

Mansoor was convicted in a secret trial in 2017 of damaging the country’s unity and sentenced to 10 years in jail. He is now held in solitary confinement, his health declining, a person familiar with the matter said.

Mansoor’s wife, Nadia, has lived in social isolation in Abu Dhabi. Neighbors are avoiding her out of fear security forces are watching.

They are correct. By June 2017 Raven had tapped into her mobile device and given her the code name Purple Egret, program documents reviewed by Reuters show.

To do so, Raven utilized a powerful new hacking tool called Karma, which allowed operatives to break into the iPhones of users around the world.

Karma allowed Raven to obtain emails, location, text messages and photographs from iPhones simply by uploading lists of numbers into a preconfigured system, five former project employees said. Reuters had no contact with Mansoor’s wife.

Karma was particularly potent because it did not require a target to click on any link to download malicious software. The operatives understood the hacking tool to rely on an undisclosed vulnerability in Apple’s iMessage text messaging software.

In 2016 and 2017, it would be used against hundreds of targets across the Middle East and Europe, including governments of Qatar, Yemen, Iran and Turkey, documents show. Raven used Karma to hack an iPhone used by the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, as well as the phones of close associates and his brother. The embassy of Qatar in Washington did not respond to requests for comment.

WHAT WASHINGTON KNEW

Former Raven operatives believed they were on the right side of the law because, they said, supervisors told them the mission was blessed by the U.S. government.

Although the NSA wasn’t involved in day-to-day operations, the agency approved of and was regularly briefed on Raven’s activities, they said Baier told them.

CyberPoint founder Gumtow said his company was not involved in hacking operations.

“We were not doing offensive operations. Period,” Gumtow said in a phone interview. “If someone was doing something rogue, then that’s painful for me to think they would do that under our banner.”

Instead, he said, the company trained Emiratis to defend themselves through a program with the country’s Ministry of Interior.

A review of internal Raven documents shows Gumtow’s description of the program as advising the Interior Ministry on cyber defense matches an “unclassified cover story” Raven operatives were instructed to give when asked about the project. Raven employees were told to say they worked for the Information Technology and Interoperability Office, the program document said.

Providing sensitive defense technologies or services to a foreign government generally requires special licenses from the U.S. State and Commerce Departments. Both agencies declined to comment on whether they issued such licenses to CyberPoint for its operations in the UAE. They added that human rights considerations figure into any such approvals.

But a 2014 State Department agreement with CyberPoint showed Washington understood the contractors were helping launch cyber surveillance operations for the UAE. The approval document explains CyberPoint’s contract is to work alongside NESA in the “protection of UAE sovereignty” through “collection of information from communications systems inside and outside the UAE” and “surveillance analysis.”

One section of the State Department approval states CyberPoint must receive specific approval from the NSA before giving any presentations pertaining to “computer network exploitation or attack.” Reuters identified dozens of such presentations Raven gave to NESA describing attacks against Donaghy, Mansoor and others. It’s unclear whether the NSA approved Raven’s operations against specific targets.

The agreement clearly forbade CyberPoint employees from targeting American citizens or companies. As part of the agreement, CyberPoint promised that its own staff and even Emirati personnel supporting the program “will not be used to Exploit U.S. Persons, (i.e. U.S. citizens, permanent resident aliens, or U.S. companies.)” Sharing classified U.S. information, controlled military technology, or the intelligence collection methods of U.S. agencies was also prohibited.

Gumtow declined to discuss the specifics of the agreement. “To the best of my ability and to the best of my knowledge, we did everything as requested when it came to U.S. rules and regulations,” he said. “And we provided a mechanism for people to come to me if they thought that something that was done was wrong.”

An NSA spokesman declined to comment on Project Raven.

A State Department spokesman declined to comment on the agreement but said such licenses do not authorize people to engage in human rights abuses.

By late 2015, some Raven operatives said their missions became more audacious.

For instance, instead of being asked to hack into individual users of an Islamist Internet forum, as before, the American contractors were called on to create computer viruses that would infect every person visiting a flagged site. Such wholesale collection efforts risked sweeping in the communications of American citizens, stepping over a line the operators knew well from their NSA days.

U.S. law generally forbids the NSA, CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies from monitoring U.S. citizens.

Working together with managers, Stroud helped create a policy for what to do when Raven swept up personal data belonging to Americans. The former NSA employees were instructed to mark that material for deletion. Other Raven operatives would also be notified so the American victims could be removed from future collection.

As time went on, Stroud noticed American data flagged for removal show up again and again in Raven’s NESA-controlled data stores.

Still, she found the work exhilarating. “It was incredible because there weren’t these limitations like there was at the NSA. There wasn’t that bullshit red tape,” she said. “I feel like we did a lot of good work on counterterrorism.”

DARKMATTER AND DEPARTURES

When Raven was created in 2009, Abu Dhabi had little cyber expertise. The original idea was for Americans to develop and run the program for five to 10 years until Emirati intelligence officers were skilled enough to take over, documents show. By 2013, the American contingent at Raven numbered between a dozen and 20 members at any time, accounting for the majority of the staff.

In late 2015, the power dynamic at the Villa shifted as the UAE grew more uncomfortable with a core national security program being controlled by foreigners, former staff said. Emirati defense officials told Gumtow they wanted Project Raven to be run through a domestic company, named DarkMatter.

Raven’s American creators were given two options: Join DarkMatter or go home.

At least eight operatives left Raven during this transition period. Some said they left after feeling unsettled about the vague explanations Raven managers provided when pressed on potential surveillance against other Americans.

DarkMatter was founded in 2014 by Faisal Al Bannai, who also created Axiom, one of the largest sellers of mobile devices in the region. DarkMatter markets itself as an innovative developer of defensive cyber technology. A 2016 Intercept article reported the company assisted UAE’s security forces in surveillance efforts and was attempting to recruit foreign cyber experts.

The Emirati company of more than 650 employees publicly acknowledges its close business relationship to the UAE government, but denies involvement in state-backed hacking efforts.

Project Raven’s true purpose was kept secret from most executives at DarkMatter, former operatives said.

DarkMatter did not respond to requests for comment. Al Bannai and the company’s current chief executive, Karim Sabbagh, did not respond to interview requests. A spokeswoman for the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined to comment.

Under DarkMatter, Project Raven continued to operate in Abu Dhabi from the Villa, but pressure escalated for the program to become more aggressive.

Before long, senior NESA officers were given more control over daily functions, former Raven operatives said, often leaving American managers out of the loop. By mid-2016, the Emirates had begun making an increasing number of sections of Raven hidden from the Americans still managing day-to-day operations. Soon, an “Emirate-eyes only” designation appeared for some hacking targets.

FBI QUESTIONS

By 2016, FBI agents began approaching DarkMatter employees reentering the United States to ask about Project Raven, three former operatives said.

The FBI wanted to know: Had they been asked to spy on Americans? Did classified information on U.S. intelligence collection techniques and technologies end up in the hands of the Emiratis?

Two agents approached Stroud in 2016 at Virginia’s Dulles airport as she was returning to the UAE after a trip home. Stroud, afraid she might be under surveillance by the UAE herself, said she brushed off the FBI investigators. “I’m not telling you guys jack,” she recounted.

Stroud had been promoted and given even more access to internal Raven databases the previous year. A lead analyst, her job was to probe the accounts of potential Raven targets and learn what vulnerabilities could be used to penetrate their email or messaging systems.

Targets were listed in various categories, by country. Yemeni targets were in the “brown category,” for example. Iran was gray.

One morning in spring 2017, after she finished her own list of targets, Stroud said she began working on a backlog of other assignments intended for a NESA officer. She noticed that a passport page of an American was in the system. When Stroud emailed supervisors to complain, she was told the data had been collected by mistake and would be deleted, according to an email reviewed by Reuters.

Concerned, Stroud began searching a targeting request list usually limited to Raven’s Emirati staff, which she was still able to access because of her role as lead analyst. She saw that security forces had sought surveillance against two other Americans.

When she questioned the apparent targeting of Americans, she received a rebuke from an Emirati colleague for accessing the targeting list, the emails show. The target requests she viewed were to be processed by “certain people. You are not one of them,” the Emirati officer wrote.

Days later, Stroud said she came upon three more American names on the hidden targeting queue.

Those names were in a category she hadn’t seen before: the “white category” — for Americans. This time, she said, the occupations were listed: journalist.

“I was sick to my stomach,” she said. “It kind of hit me at that macro level realizing there was a whole category for U.S. persons on this program.”

Once more, she said she turned to manager Baier. He attempted to downplay the concern and asked her to drop the issue, she said. But he also indicated that any targeting of Americans was supposed to be done by Raven’s Emirate staff, said Stroud and two other people familiar with the discussion.

Stroud’s account of the incidents was confirmed by four other former employees and emails reviewed by Reuters.

When Stroud kept raising questions, she said, she was put on leave by superiors, her phones and passport were taken, and she was escorted from the building. Stroud said it all happened so quickly she was unable to recall the names of the three U.S. journalists or other Americans she came across in the files. “I felt like one of those national security targets,” she said. “I’m stuck in the country, I’m being surveilled, I can’t leave.”

After two months, Stroud was allowed to return to America. Soon after, she fished out the business card of the FBI agents who had confronted her at the airport.

“I don’t think Americans should be doing this to other Americans,” she told Reuters. “I’m a spy, I get that. I’m an intelligence officer, but I’m not a bad one.”

By Christopher Bing and Joel Schectman in Washington. Editing by Ronnie Greene, Jonathan Weber and Michael Williams

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

Apple has disabled the group calling function of FaceTime while it pushes out its update to customers

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

Apple has disabled the group calling function of FaceTime while it pushes out its update to customers

Dan Coats, the U.S. director of national intelligence, testifies before the Senate Intelligence Committee. (Source: PBS)

Dan Coats, the U.S. director of national intelligence, testifies before the Senate Intelligence Committee. (Source: PBS) Source: Worldwide Threat Assessment

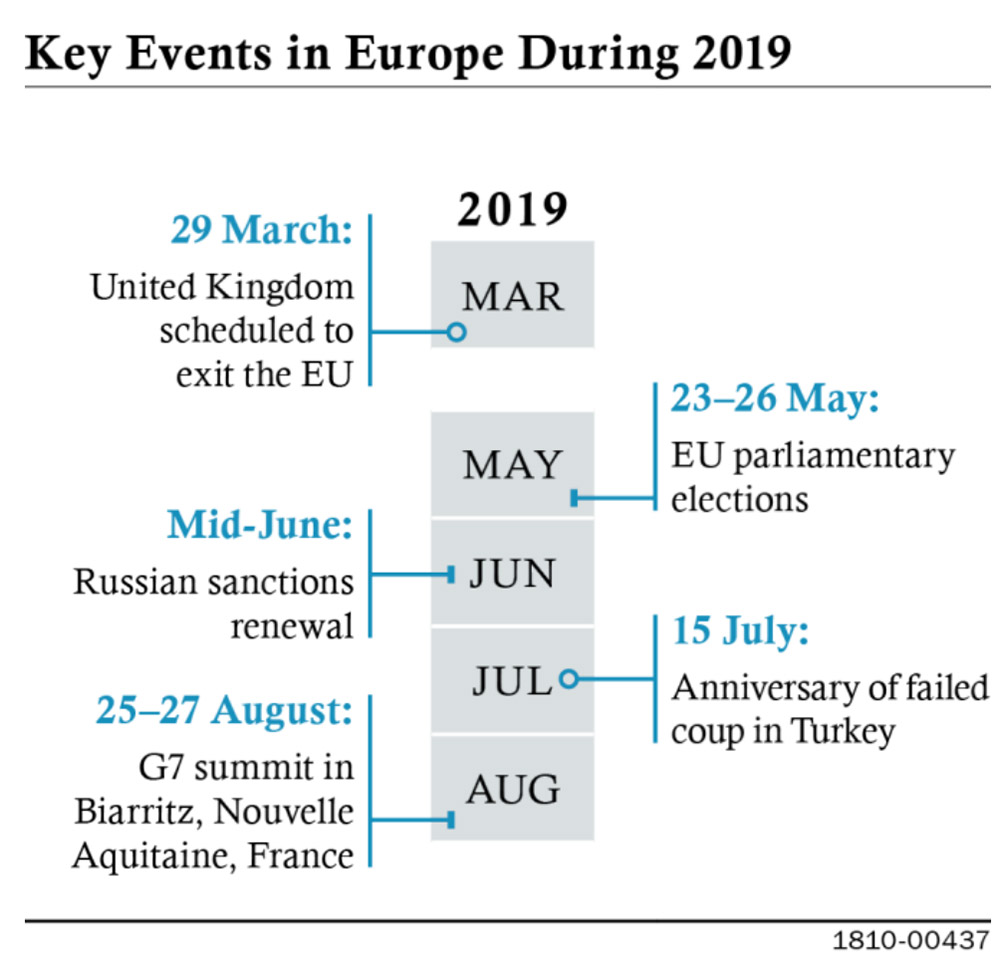

Source: Worldwide Threat Assessment Photo:

Photo:  District Judge Lucy H. Koh

District Judge Lucy H. Koh

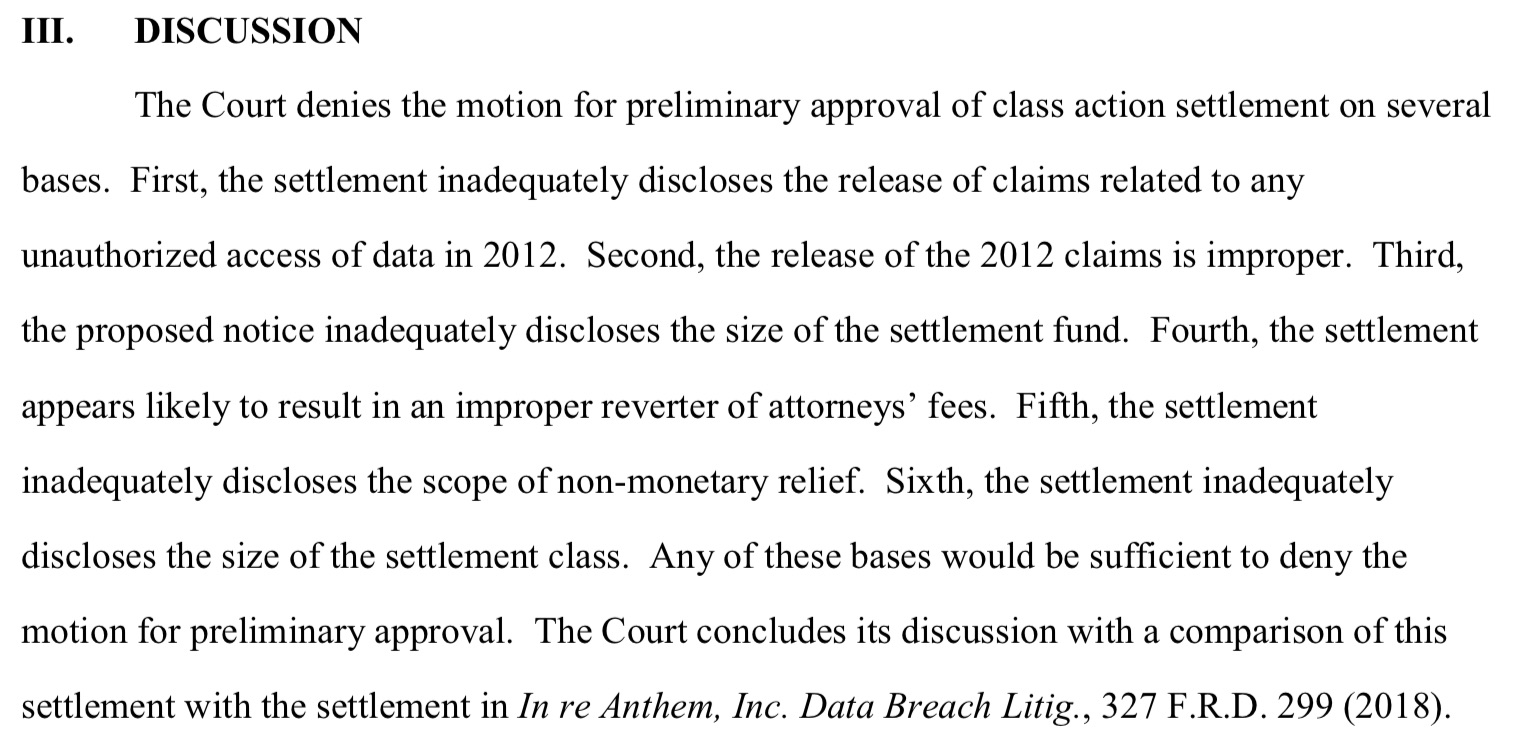

Koh's order lists her six reasons for rejecting the proposed settlement.

Koh's order lists her six reasons for rejecting the proposed settlement.