Encryption , Forensics , Mobility

Both Sides Appeal to Public, but Legal Battle Could Take Years

The war of words continues to heat up between the Justice Department and Apple over the FBI's request that the technology provider help it unlock an iPhone - bypassing its encryption - that was seized during the course of an investigation.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Sheri Pym ordered Apple on Feb. 16 to assist the FBI. But Apple CEO Tim Cook says the company will fight that order. "This case is about much more than a single phone or a single investigation," Cook says in a Feb. 22 email to Apple's employees, Reuters reports. "At stake is the data security of hundreds of millions of law-abiding people, and setting a dangerous precedent that threatens everyone's civil liberties."

But many security and legal watchers say that if the Department of Justice - of which the FBI is part - chose this case to create a legal precedent for compelling technology firms to unlock their devices with a court order, then it's chosen well. The phone in question was used in the Dec. 2 attack in San Bernardino, Calif., by one of the shooters: Syed Rizwan Farook (see DOJ: Apple Puts Marketing Before Law).

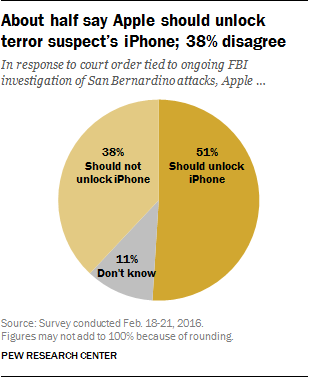

Indeed, Pew Research Center surveyed 1,002 U.S. adults from Feb. 18 to 21, and found that 51 percent believe Apple should unlock the iPhone to aid the FBI's investigation, while 38 percent believe it should not, to better protect the security of everyone's information. Those proportions held even with the 39 percent of the public who believed they'd heard quite a lot about the case.

FBI Director: 'Follow this Lead'

In an article published Feb. 21, FBI Director James Comey defended the bureau's request as relating to a single device, suggesting any legal precedent would soon become outdated as technology evolves. "We simply want the chance, with a search warrant, to try to guess the terrorist's passcode without the phone essentially self-destructing and without it taking a decade to guess correctly," he says. "That's it."

The FBI isn't hesitating to try and push every button at its disposal, with Comey, for example, peppering words such as "heartbreaking," "innocents" and "slaughtered," throughout his post, or portraying the investigation as a moral imperative. "We don't want to break anyone's encryption or set a master key loose on the land," he says. "We can't look the survivors in the eye, or ourselves in the mirror, if we don't follow this lead."

Missed Opportunities

But the case is far from clear cut, and the FBI's current legal strategy appears to have resulted from wrong turns and missed opportunities. On the technical front, notably, Farook's iPhone 5C was issued to him by his employer, San Bernardino County. While the county was testing mobile device management software from MobileIron that could have been used to unlock the phone, Farook's department hadn't signed up, Reuters reports.

San Bernardino County officials, meanwhile, say they changed Farook's iCloud password at the FBI's request. But Apple says that the FBI could have unlocked the phone if it hadn't done that and imaged what was stored on the device, via an iCloud backup, and that it recommended against that approach during the investigation. "One of the strongest suggestions we offered was that they pair the phone to a previously joined network, which would allow them to back up the phone and get the data they are now asking for," Apple says in a FAQ about the court case. "Unfortunately, we learned that while the attacker's iPhone was in FBI custody the Apple ID password associated with the phone was changed. Changing this password meant the phone could no longer access iCloud services."

The County was working cooperatively with the FBI when it reset the iCloud password at the FBI's request.

Security experts tell ABC that the phone could likely be unlocked by using a technique called "de-capping" - described as "removing and de-capsulating the phone's memory chip to expose it to direct, microscopic scrutiny and exploitation" - but that digital forensic technique isn't foolproof.

Forensic Expert: FBI Needs Images

Meanwhile, forensic scientist Jonathan Ździarski, author of "iPhone Forensics," notes in a blog post that the FBI says it's now seeking help to unlock Farook's iPhone. But from an evidence-gathering perspective - meaning, gathering evidence that will stand up in court - he says that is the wrong approach. That's because unlocking the phone could allow background apps to launch, thus overwriting or changing data that's stored on the device. Instead, he says, investigators should be focusing on creating a disk image of what's currently on the device.

"[The] FBI would have to really crawl into the dumpster to think that using the device's user interface is a viable solution to analyze evidence," he says. "Not only does it run the strong risk of destroying the only copy of evidence they might have, but any smart judge would throw out any case using such sloppy techniques."

Is Encryption Like Free Speech?

Complicating the Justice Department's move to compel Apple to unlock the phone, however, are a number of constitutional-rights questions, says Andrew Keane Woods, an assistant professor of law at University of Kentucky College of Law.

For starters, Apple might argue that the FBI's request violates free-speech rights. "Code can be a form of speech," Woods says in a blog post for Lawfare. "The lock-swapping mechanism required in this case would require Apple's engineers to sit down at a computer and start writing. And that action, as courts recognized long ago, is speech."

Of course, that's just one potential defense that Apple may mount, Woods says. But as he highlights, "the constitutional issues in this case are not trivial," and this particular court battle is "only the beginning - really, it is just the end of the first act - of a long debate about the proper scope of government authority over the digital tools that we use to communicate."

Who Should Win?

So who's right: Apple, the FBI, or a bit of both? "It's too early to tell who should win," says computer crime and surveillance law expert Orin Kerr, a professor of law at the George Washington University Law School, in a recent Washington Post op-ed.

So far, he says, Apple hasn't yet filed its objections to the federal magistrate judge's "tentative" order that it comply with the FBI's request. It's expected to do so by Feb. 26, Reuters reports. And a related hearing has been scheduled for March 22. But that will likely just be the beginning of a long process that "will work its way from the magistrate judge to a district judge and then to the court of appeals," Kerr says.

"Ordinarily, that would take around two years," he adds.

Memo to journalists: When case is about law, and appeal guaranteed, it doesn't matter how trial judge rules. Appellate court takes new look.