Encryption , Risk Management , Technology

4.5 Million Embedded Systems Reuse Crypto Keys, SEC Consult Warns SEC Consult says embedded systems that reuse cryptographic keys include the ToughSwitch from Ubiquiti Networks

SEC Consult says embedded systems that reuse cryptographic keys include the ToughSwitch from Ubiquiti NetworksInternet of Things alert: Many embedded systems contain hardcoded cryptographic credentials that attackers can use to seize control of the devices or crack encrypted website traffic. And the problem is only getting worse.

See Also: Managing Identity, Security and Device Compliance in an IT World

So says SEC Consult, a Vienna-based application security services and information security consultancy, in a new report that analyzes internet-connected embedded systems, referring to any type of system that uses software that's been embedded into hardware. It warns that many of those Internet of Things systems - including "Internet gateways, routers, modems, IP cameras, VoIP phones" and more - use private HTTPS and Secure Shell (SSH) keys that are not secret.

The report, from Stefan Viehböck, a senior security consultant at SEC Consult, builds on research that he released in November 2015, which involved analyzing cryptographic keys - public keys, private keys and certificates - contained in the firmware used to run more than 4,000 embedded devices from more than 70 vendors. In particular, he reviewed SSH host keys, which allow remote access to an SSH server, as well as X.509 certificates, which are used to facilitate HTTPS connections that encrypt web traffic.

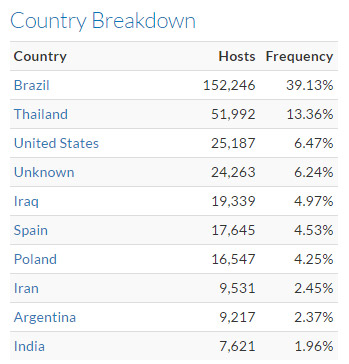

Last year, SEC Consult warned it found that 580 unique, private HTTPS keys were being reused by 9 percent of all HTTPS hosts on the web and 6 percent of all SSH hosts on the web. The consultancy began working with the U.S. Computer Emergency Response Team in August 2015 to notify 50 affected vendors and ISPs. It hoped to trigger firmware upgrades from affected vendors as well as a concerted push to update vulnerable devices. Many such devices are customer premises equipment, referring to gear that gets installed on-site by ISPs or systems integrators.

But whereas the firm found 3.2 million devices using known private HTTPS keys nine months ago, recent scans have revealed that there are now 4.5 million such devices - an increase of 40 percent.

Clearly, the problem is getting worse, at least where HTTPS private certificates are concerned. The researchers haven't yet been able to run a new SSH host key test yet, although say they hope to do so soon.

Hundreds of certificates, SSH host keys +matching private keys found in embedded firmware: https://t.co/PCBGxFEfO1 pic.twitter.com/7LGRyvxubn

To help organizations identify related vulnerabilities, develop countermeasures - and no doubt pressure culpable vendors and ISPs - SEC Consult has released all 580 static keys via the code-sharing site GitHub. "Releasing the private keys is not something we take lightly as it allows global adversaries to exploit this vulnerability class on a large scale," Viehböck says. "However, we think that any determined attacker can repeat our research and get the private keys from publicly available firmware with ease.

Key Reuse: What's the Risk?

Reusing private keys poses numerous risks. Attackers that obtain a private HTTPS key used by a system could launch man-in-the-middle attacks against the device, including decrypting HTTPS traffic. Attackers who obtain a private SSH key for a system, meanwhile, could potentially authenticate to a remote device - gaining encrypted, admin-level access - and take it over, as well as potentially use it as a launching pad for hacking into other devices on the network.

In 2015, security experts began warning that tens of thousands of devices that run on ARM processors, including devices built by Ubiquiti, were being exploited by variants of MrBlack - a.k.a. Spike - botnet-building malware.

Ubiquity Networks devices that reuse crypto keys. Source: SEC Consult, using data from Censys.

Ubiquity Networks devices that reuse crypto keys. Source: SEC Consult, using data from Censys.In May, meanwhile, security firm Symantec released a report detailing how thousands of Ubiquiti AirOS routers running outdated firmware appeared to be getting hacked by malware that adds a backdoor to systems, giving attackers remote access.

"Any router that runs older versions of the firmware and has its HTTP/HTTPS interface exposed to the internet could be infected," Symantec said. "Ubiquiti released a patch for this vulnerability almost a year ago. However, as is often the case on these devices, many routers may still have old firmware installed."

Default credentials may also be to blame. "While investigating this threat, we identified attempts to log into our honeypot routers over Secure Shell (SSH) using the default Ubiquiti credentials (username: ubnt and password: ubnt)," Symantec says. "Data from our honeypots shows that these credentials are among the top five that attackers use to try and break into routers."

Pwn All the Things

Viehböck notes that numerous users of Ubiquiti Networks' equipment still appear to be struggling to eliminate malware from their devices (see Router Hacks: Who's Responsible?).

"Ubiquiti has even started to include functionality to remove malware in their firmware updates and released a standalone tool called 'CureMalware' that promises removal of the botnets Skynet, PimPamPum and ExploitIM," he says. "The tool comes with the helpful instructions," including the malware-imposed expletive-derived username and password that users must enter to regain control of their devices from the worm detailed by Symantec.

On the upside, Viehböck says, whereas he counted 1.1 million public-facing, internet-connected Ubiquiti devices in November 2015, that number has since dropped to 410,000. "The bad news is that the major drop is likely caused by various botnets that exploit weak credentials as well as critical vulnerabilities, including an innocently titled "arbitrary file upload" vulnerability [that enables] straightforward remote code execution." A related attack module is freely available as well via the free, open source penetration testing toolkit Metasploit. Viehböck surmises that ongoing attacks against the devices have led users to safeguard them with firewalls, which is why they're not showing up in his internet scans anymore.

"What a mess," Viehböck says, "and Ubiquiti still has remote management on the WAN port enabled by default."

Ubiquiti did not immediately reply to Information Security Media Group's request for comment.

SEC Consult says that Ubiquiti is not the only vendor or ISP at fault. It claims its research also discovered numerous vulnerable devices being shipped via other vendors and ISPs, including 500,000 devices from CenturyLink in the U.S; more than 1 million from Mexico's TELEMEX; 170,000 from Telefónica in Spain, 100,000 from China Telecom, 55,000 from Chile's VTR Globalcom, 45,000 from Chunghwa Telecom in Taiwan and more than 26,000 from Telstra in Australia.

How Vendors Must Respond

Viehböck says the solution to the key reuse problem is no secret. "Vendors should make sure that each device uses random, unique cryptographic keys," he says. "These can be computed in the factory or on first boot. In the case of [customer premises equipment] devices, both the ISP and the vendor have to work together to provide fixed firmware for affected devices."

One reason so many devices reuse keys is that many systems integrators and ISPs prefer devices that can be easily accessed remotely, both to initially configure the device as well as provide ongoing troubleshooting. But security experts have long warned that devices that ship with default configurations - including on-by-default remote access - too often get deployed with those defaults intact.

Viehböck recommends that if an ISP or systems integrator requires remote access to a device, it should not allow remote access to the device's wide-area-network port, but instead use a VLAN with "strict" access control lists.

For enterprise end users, whenever possible, "change the SSH host keys and X.509 certificates to device-specific ones," Viehböck says. For vulnerable devices where this isn't possible, or for "a regular home user" who will likely lack the required technical knowledge - and fortitude - to undertake the required steps, the only other recourse may be to throw away the device and buy a new one.

Many enterprises and home users, however, don't junk outdated - and thus potentially exploitable - devices. Last month, for example, security researchers counted at least 15,000 Cisco PIX devices still in use, despite Cisco ceasing support in 2013 and having recommended since 2008 that users upgrade to its Adaptive Security Appliance devices range. As a result, at least some of those devices appear to have been hacked by cybercrime gangs as well as intelligence agencies to access corporate networks (see NSA Pwned Cisco VPNs for 11 Years).