Anti-Malware , Fraud , Technology

Following the Cryptocurrency: Could Police Do More? A CryptoWall ransom demand.

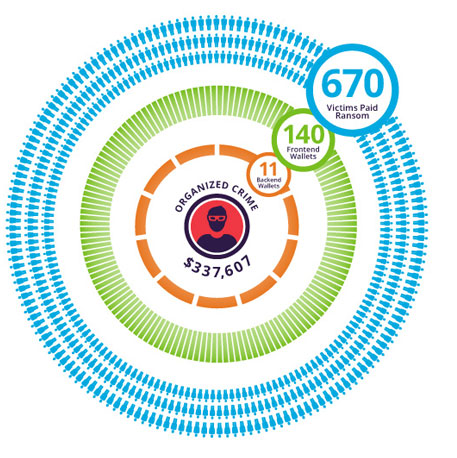

A CryptoWall ransom demand.Over a three-month period in 2015, a single cybercrime gang managed to earn at least $330,000 in bitcoins thanks to an estimated 670 victims paying attackers' ransom demand to decrypt their ransomware-infected systems.

See Also: Public, Private & Hybrid Cloud: Why Compliance (Done Right) is the Easy Part

That finding comes via a new report issued by security firm Imperva, which analyzed the bitcoin wallets to which the gang's ransom demands were transferred, from May 2015 to July 2015.

Imperva's report centers on CryptoWall 3.0, although CryptoWall 4.0 debuted in November 2015 (see Malware Hides, Except When It Shouts). But the researchers say that despite some technical improvements, "the ransom collection method largely remains the same." In particular, the gang demanded that victims use the Tor anonymizing browser to pay ransoms - worth $500 to $700 in bitcoins - to help disguise related transactions. Imperva says the ransomware appeared to infect systems after victims opened a malicious PDF - disguised as a resume - which executed the malware.

The gang's CryptoWall infections also studied victims' location before setting the ransom-demand amount. "The ransom amount for the USA is $700 whereas for Israel, Russia, and Mexico, it's only $500," Imperva says. "The malware authors clearly know average incomes, and change ransom demands based on geolocation to keep the payments affordable."

The precise number of total bitcoins traced to the gang - worth $330,607 - no doubt represents only part of the gang's haul, Amichai Shulman, Imperva's co-founder and chief technology officer, tells Information Security Media Group. "We think that figure is small, based on the number of transactions we've been able to see and map," he says. "However, it is possible that by applying some more mapping algorithms through bitcoin's blockchain, we would get to more transactions."

Source: Imperva

Source: Imperva

Globally, CryptoWall 3.0, which emerged in early 2015, has been tied to more than $325 million in losses (see Refined Ransomware Streamlines Extortion).

In June 2015, the Internet Crime Complaint Center - a collaboration between the FBI and the National White Collar Crime Center - said it received 992 CryptoWall-related complaints between April 2014 and June 2015. Losses related to the attacks cost U.S. businesses and consumers more than $18 million, the IC3 noted (see FBI Alert: $18 Million in Ransomware Losses).

Imperva says the ability to trace ransom payments back to specific bitcoin wallets - as it has done - begs the question of whether law enforcement agencies should be doing more to target these gangs. "The trend is that the ransomware business is growing uncontrollably without law enforcement intervention," Shulman says.

Many Bitcoin Misperceptions

Numerous misconceptions about bitcoin persist. "Probably the biggest is that if you transact using bitcoin you can do so with total anonymity," says University of Surrey computer science professor Alan Woodward in a blog post. In fact, "[many] bitcoin users are confusing anonymity with pseudonymity." That's because every bitcoin transaction gets posted to the public blockchain. While law enforcement agencies are unsurprisingly cagey about their analytical capabilities, experts say they likely have advanced techniques for tying accounts to suspects and "following the cryptocurrency money" (see Tougher to Use Bitcoin for Crime?).

Nor is using Tor a magic bullet for hiding illegal bitcoin transactions. "The IP address from which the transaction hails could easily be obscured using something such as Tor, but ... Tor itself does not guarantee anonymity," says Woodward, who also advises the EU's law enforcement intelligence agency, Europol, on cybersecurity.

Yet another misconception - arguably including on the part of the Imperva researchers - is that identifying the user, or users, behind a specific bitcoin wallet makes it possible to immediately disrupt their activities. In fact, security experts say that many online crime gangs are based in locations such as Russia, which has never extradited a cybercrime suspect. The country is also renowned for turning a blind eye to hacking-related activities, provided hackers don't target organizations in Russia, and do occasionally assist government agencies (see Russian Cybercrime Rule No. 1: Don't Hack Russians).

"It is one thing identifying who the criminals are, it is entirely another thing to have enough evidence to prove in a court of law they committed the crimes," says information security consultant Brian Honan, who's also a Europol cybersecurity adviser. "In addition, the criminals may be located in jurisdictions that do not have adequate computer crime laws in place or in ones that do not cooperate with western law enforcement."

Ransom-demanding attackers haven't been getting away with their attacks scot-free. In June 2014, police announced that they'd busted the gang behind the Gameover Zeus malware and CryptoLocker ransomware. In October 2015, a cybercrime gang tied to Angler ransomware - and $34 million in annual ransom profits - was disrupted by security researchers. And two months later, as part of an ongoing investigation, police arrested two suspected members of the notorious "DDoS for Bitcoin" - or DD4BC - gang that threatened distributed denial-of-service attacks against organizations unless they paid an extortion demand (see Cyber Extortion: Fighting DDoS Attacks).

Low Barriers to Entry

Even so, the barrier to entry for would-be ransomware attackers continues to be low. In November 2015, threat analyst Liviu Arsene at security vendor BitDefender reported that a version of the CryptoWall 3.1 ransomware kit - including source code and free support - was being sold for $3,000 worth of bitcoins.

Debate also continues to rage over whether victims should pay ransoms. Many information security experts and law enforcement agencies argue that ransoms should never be paid (see Irish Cybercrime Conference Targets Top Threats).

But Joseph Bonavolonta, the assistant special agent in charge of the FBI's Cyber and Counterintelligence Program in its Boston office, sparked controversy in October 2015 when he suggested otherwise, given the near-impossibility of otherwise decrypting so many ransomware infections. "The ransomware is that good," Bonavolonta reportedly said. "To be honest, we often advise people just to pay the ransom."

The FBI did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Executive Editor Mathew J. Schwartz also contributed to this story.