A previously unknown cybercrime group has hacked into numerous organizations in the retail and hospitality sectors to steal an estimated 20 million payment cards, collectively worth an estimated $400 million via underground cybercrime forum sales, according to the cybersecurity firm FireEye.

See Also: How to Illuminate Data Risk to Avoid Financial Shocks

In a new report, FireEye says the group, which it's dubbed FIN6, steals credit card data and then sells it on darknet carder forums to buyers who use the payment card data to commit fraud.

While many other cybercrime groups take a similar approach, FIN6 excels in its unprecedented speed to market, says Richard Turner, FireEye's Europe, Middle East and Africa president. "As far as we can tell, this is the first group that has really put an effort into ensuring that they get the credentials to market as quickly and as efficiently as they can to maximize the premium price that those credentials will generate," he says. "They can deliver them to market quite quickly to enable people to commit their crimes more quickly."

The value of stolen card data on carder forums has long been tied to the freshness of that data. Maximum freshness comes with stolen card data that issuers don't yet know has been stolen. But as issuers spot card fraud and trace it back to particular e-commerce sites or physical locations, then identify likely breach periods, the freshness of that data naturally decays. As a result, sellers can no longer command premium prices for the data, because fewer card numbers will work for buyers.

As a result, there's a natural economic incentive for cybercrime groups to bring their cards to market as quickly as possible. "This is just a really good example of [how] our adversaries are not spotted youths in back rooms," Turner says. "They're well-skilled, well-resourced, intelligent people who have a mission to create and generate wealth by illegal means, and by defrauding companies. And they're just maturing, to say, 'How do I maximize my return on investment?' It makes a lot of sense. It's just such a shame that the effort isn't being put into more intellectual [and beneficial] efforts."

Top Targets: Hospitality, Retail

Turner says cybercrime groups typically target whatever is the weakest point in an organization's defenses. Their efforts typically involve targeted spear-phishing attacks, directly hacking into a targeted organization or gaining access via a connected network, for example, via a poorly secured supply chain partner, he says.

Whatever method is used, Turner says, the goal is to install point-of-sale malware and siphon off as many card details as possible. In the case of FIN6, the POS malware of choice appears to be Trinity, also known as FrameworkPOS.

In today's increasingly specialized cybercrime economy, while groups such as FIN6 steal card data, they don't use it themselves to commit fraud, but instead monetize the attacks by selling the card data to others (see Banks Reacting Faster to Card Breaches). As a result, a related breach might be well underway - or already over - by the time the fraud gets flagged.

The Lure of 'Reshipping Mule' Scams

The importance of bringing fresh card data to market quickly is tied to how fraudsters put that data to work. In the past, they often purchased stolen card data and attempted to use it to directly withdraw money; engaged money mules to withdraw money or buy and sell goods, and then wire the money to attacker-controlled bank accounts; or directly purchased high-value goods and tried to ship them overseas.

But the first two approaches involve a measure of physical risk - and trust - while the latter method has become less effective because many U.S.-based online retailers block shipments to certain geographies, including Russia and Ukraine, according to a new report from security researchers at Hewlett Packard Enterprise.

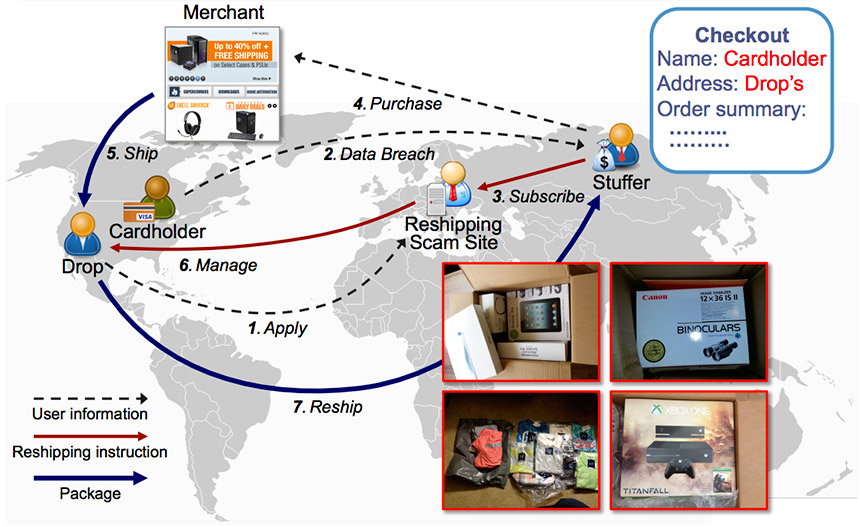

As a result, many fraudsters have been turning to so-called "reshipping mule scams," which are less risky as well as harder to block. Such scams involve a "stuffer" purchasing goods with the stolen card data, then shipping them to a neutral "drop" address - often, someone recruited via a "work at home" scam - after which the recipient sends the goods on to criminals, who then resell the items on the black market, or sometimes via legitimate sites, to turn a profit.

"Due to the intricacies of this kind of scam, it is exceedingly difficult to trace, stop and return shipments, which is why reshipping scams have become a common means for miscreants to turn stolen credit cards into cash," according to "Drops for Stuff: An Analysis of Reshipping Mule Scams," a research paper that was presented at the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security in October 2015. The paper is based on work undertaken by a team of researchers, including University of California at Santa Barbara information security researcher Shuang Hao.

Anatomy of a Reshipping Scam Operation

Source: "Drops for Stuff: An Analysis of Reshipping Mule Scams"

Source: "Drops for Stuff: An Analysis of Reshipping Mule Scams"The researchers estimate that a single reshipping site earns $7.3 million, on average, every year, and that the overall market earns $1.8 billion annually (see I Believe in Cybercrime Unicorns).

Some criminal groups are even offering "reshipping as a service," which they sell by either taking up to 50 percent of the profits, for high-value items, or charging a flat rate - typically $50 to $70 per package - for lower-value products, the researchers say.

All Roads Leads to Eastern Europe?

"Most drops are located in the United States, as most targeted retailers as well as stolen credit card data originate here," according to the Hewlett Packard Enterprise report. But the researchers also found one reshipping service targeting Germany-based online retailer Zalando.de.

The researchers found that of the reshipping scam sites they studied, 85 percent of all packages were shipped to either Moscow or its suburbs.

FireEye, in its report on FIN6, doesn't attribute the crimes perpetrated by the card data hacking specialists to a specific set of individuals or a region. But FireEye's Turner says the company suspects the group is operating from Eastern Europe.