Anti-Malware , Encryption , Endpoint Security

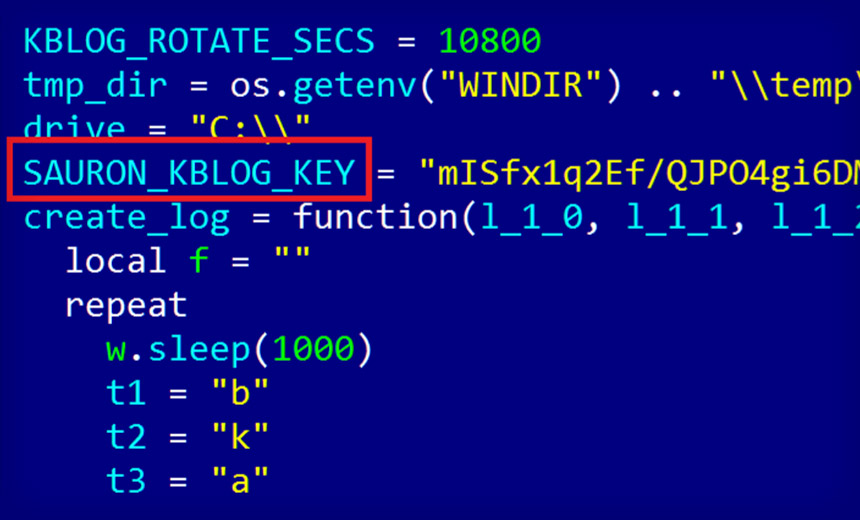

Active Cyber-Espionage Campaign Dates From 2011, Security Firms Warn The group's malware references "Sauron" in its configuration files

The group's malware references "Sauron" in its configuration filesSecurity researchers are warning that they've discovered a highly advanced and targeted cyber-espionage campaign that appears to have been running since 2011, and which remains active. The APT malware used by the group behind the campaign is remarkable in part not only for having remained undetected for so long, but also for its ability to exfiltrate data from air-gapped networks using multiple techniques, including by piggybacking on network protocols, researchers say.

See Also: How to Mitigate Credential Theft by Securing Active Directory

Based on a reference to "Sauron" in the malware configuration files, the APT campaign has been dubbed "ProjectSauron" by Kaspersky Lab - referring to an all-seeing villain "The Lord of the Rings" - as well as "Strider" by Symantec, referring to a character who fights against Sauron.

Kaspersky Lab, in an Aug. 8 blog post, says it first discovered related attacks in September 2015, after finding "anomalous network traffic in a government organization network," which it ultimately traced to malware that it describes as being "a top-of-the-top modular cyber-espionage platform."

The government target has not been named, although the security firm says that it's found more than 30 infected organizations in Russia, Iran and Rwanda, although believes that's "just a tiny tip of the iceberg." It adds that the ProjectSauron malware works on all modern versions of Windows, and that related infections have infected systems running Windows XP x86 as well as Windows 2012 R2 Server Edition x64, and likely everything in between.

In some cases, the malware appears to have been used to target and exfiltrate data related to "communication encryption software" used by government organizations and agencies, Kaspersky Lab says. "It steals encryption keys, configuration files, and IP addresses of the key infrastructure servers related to the software," it says, adding that the malware includes the ability to install backdoors on infected systems, record keystrokes and steal documents.

Symantec, in an Aug. 7 blog post based on data collected by its anti-virus products, says it's found 36 related infections in seven organizations, across four countries, involving "a number of organizations and individuals located in Russia, an airline in China, an organization in Sweden and an embassy in Belgium." It refers to the related malware as Remsec.

This isn't the first time that two separate security firms have issued nearly simultaneous research reports into long-running malware campaigns. But security researchers say that they often work together, and across organizational boundaries, to identify and study advanced malware campaigns (see AV Firms Defend Regin Alert Timing).

Nation State Suspected

To date, researchers don't know how this malware first infects systems, nor do they know who is responsible. But all signs point to a "very advanced actor," Kaspersky Lab says. The security firm's chief researcher, Costin Raiu, notes that the malware - written in English, although with some Italian words - rivals the sophistication of such advanced malware as Duqu, Flame, Equation and Regin. "Whether related or unrelated to these advanced actors, the ProjectSauron attackers have definitely learned from these others," the company's report says.

ProjectSauron network sniffer captures files matching these patterns. Interesting Italian keywords: pic.twitter.com/HhDFiMUn9w

The malware is designed to be stealthy, for example remaining hidden until specified network protocols awaken it. "Much of the malware's functionality is deployed over the network, meaning it resides only in a computer's memory and is never stored on disk," Symantec says. "This also makes the malware more difficult to detect."

According to a technical teardown published by Kaspersky Lab, the malware can draw on 50 different modules, all of which appear to have been customized for individual targets.

After infecting a system, the malware pretends to be a Windows Local System Authority password filter on domain controllers, which is typically used by IT administrators to enforce password policies and validate that new passwords meet specified requirements, for example, involving length or complexity. "This way, the ProjectSauron passive backdoor module starts every time any domain, local user, or administrator logs in or changes a password, and promptly harvests the passwords in plaintext," Kaspersky Lab says.

The security firm says the malware has been distributed in some organizations via legitimate scripts that system administrators use to distribute software to end users, and that the malware has been disguised with names that resemble executable filenames used by Hewlett-Packard, Kaspersky Lab, Microsoft, Symantec and VMware.

Malware Penetrates Air-Gapped Networks

One standout feature of the malware is its ability to penetrate air-gapped networks, using one of those 50 modules. Kaspersky Lab says this attack technique begins by infecting a networked system, which waits for a USB drive to be attached. When that happens, it reformats the drive to add a hidden, encrypted partition that's several hundred megabytes in size, inside which it installs its own virtual file system, which won't be recognized by a "common operating system" such as Windows.

This infected USB key is used to exfiltrate data from air-gapped systems, with the data getting grabbed back off of the device once it gets plugged into an infected, network-connected system, the researchers say.

But it's not yet clear how attackers are gaining control of the air-gapped systems themselves, which would be required before they could exfiltrate data. "There has to be another component such as a zero-day exploit placed on the main partition of the USB drive," Kaspersky Lab says. "Unfortunately we haven't found any zero-day exploit embedded in the body of any of the malware we analyzed, and we believe it was probably deployed in rare, hard-to-catch instances."

Five Years and Counting

One reason the malware has been so difficult to spot, thus far, has been attackers' customizing their malicious code so that it's unique to each victim. "The attackers clearly understand that we as researchers are always looking for patterns," Kaspersky Lab says. "Remove the patterns and the operation will be harder to discover."