Anti-Malware , Encryption , Technology

I Believe in Cybercrime Unicorns Signs Point to Cyber Gangs with $1 Billion Valuations

There's new evidence of just how much cybercrime pays.

Mikko Hyponnen, chief research officer of Helsinki-based security firm F-Secure, reports that cybercriminals using CryptoWall ransomware version 3 have collectively cleared a cool $325 million. The figure could be higher because it represents only the ill-gotten CryptoWall gains that authorities have been able to trace (see Ransomware: Are We in Denial?).

Hypponen poses this provocative question: What if some individual cybercrime gangs - using not just ransomware, but a variety of other tools and scams - have earned so much money that they've achieved the equivalent of "unicorn" status? That's venture-capitalist-speak for a startup company with a valuation of more than $1 billion.

Blockchain traffic shows that some cybercrime gangs have made hundreds of millions of dollars. Do we already have Cybercrime Unicorns?

Other security experts also suspect cybercrime unicorns are real. "I think we might well have them," says University of Surrey computer science professor Alan Woodward, who advises Europol, the association of European law enforcement agencies, on cybersecurity matters. He also co-authored its Internet Organized Crime Threat Assessment report, released in September 2015. "We included some data in the IOCTA report that showed 40 percent of all criminal-to-criminal money transfers use cryptocurrencies. If you think about how big the criminal economy is, then you can imagine how much money that represents."

Hypponen's analysis, meanwhile, is based on a report from the Cyber Threat Alliance - composed of security vendors Fortinet, Intel Security, Palo Alto Networks and Symantec - which studied some of the bitcoin blockchain activity that researchers have tied to gangs using version 3 of CryptoWall. The blockchain is a public ledger, on which all bitcoin transactions are based, and it records the sending as well as receiving bitcoin addresses for any given transaction. For example, 1AEoiHY23fbBn8QiJ5y6oAjrhRY1Fb85uc - just one of the many bitcoin addresses tied to CryptoWall-using gangs - received more than 5,300 bitcoins ($2.3 million).

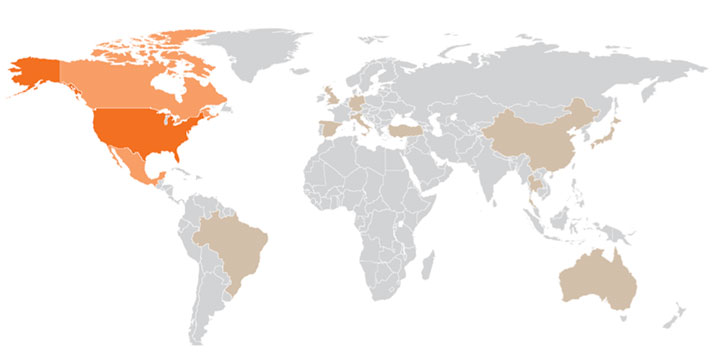

"The $325 million in damages spans hundreds of thousands of victims across the globe," the alliance's report states, noting that while North America was predominantly targeted, the most-attacked geographies all share something in common. "These countries' affluence likely contributes to them being targeted, as users located in these regions are more likely to pay the required ransom amount."

CryptoWall Hotspots

Source: Cyber Threat Alliance

Source: Cyber Threat Alliance

With that kind of money available, it's a no-brainer that criminal syndicates continue to love ransomware, which encrypts victims' hard drives and demands a payment - most often via bitcoins - to unlock it. While many think of bitcoin as being anonymous, in reality, experts say it's more accurately described as "anonymizing" (see Tougher to Use Bitcoin for Crime?).

Even so, bitcoin transactions reportedly remain tough to trace, especially for law enforcement agencies that want to "follow the money" from attack to attacker (see How Do We Catch Cybercrime Kingpins?). "We can see some correlation with certain ransomware attacks, but tracing the money once it's in the cryptocurrency ecosystem is tricky," Woodward says. "There are some tools in use by law enforcement agencies, but they don't talk about them much."

Of course, using bitcoins is just one type of money-laundering technique employed by criminals to convert their ill-stolen gains - from ransomware, online extortion or other types of crime - into what looks like legitimate earnings. "Criminals transfer money in all sorts of ways, laundering through everything from property to racehorses," Woodward says. "But not unicorns."