Breach Notification , Breach Response , Data Breach

LinkedIn's Password Fail No Site-Wide Password Reset Followed 2012 Breach

"In an abundance of caution, we are requiring all users to change their passwords."

See Also: Unlocking Software Innovation with Secure Data as a Service

After a data breach, many organizations communicate words to that effect to their customers. It's a smart move, since many breaches turn out to be much worse than initially suspected, as organizations find after launching a digital forensic investigation.

But in 2012, after 6.5 million LinkedIn users' password hashes appeared on a password-cracking forum, the social network didn't force all users to reset their passwords. That choice is now coming back to haunt LinkedIn, after an alleged cache of 167 million accounts appeared for sale on a dark web forum. Paid breach notification site Leaked Source says it was able to purchase the data for just 5 bitcoins, or about $2,200 (see LinkedIn Breach: Worse Than Advertised).

Rather belatedly - horse, barn, exit - LinkedIn says that it has locked the accounts of all users who haven't changed their passwords since 2012, requiring them to pick a new password.

When the LinkedIn breach came to light four years ago, LinkedIn - which didn't have a CISO - declined to tell me how many users might have been affected by the breach or breaches that obtained the credentials. But LinkedIn did at least lock some accounts.

"At the time, our immediate response included a mandatory password reset for all accounts we believed were compromised as a result of the unauthorized disclosure," LinkedIn CISO Cory Scott, who joined the company in 2013, says in a blog post. "Additionally, we advised all members of LinkedIn to change their passwords as a matter of best practice."

Now, of course, the size of the data dump suggests that attackers may have obtained every last LinkedIn user's credentials. And since the credentials' release, some buyers have reportedly already been putting them to use, taking over high-profile accounts and potentially using reused credentials to access victims' accounts on other services. And who knows what the data was being used for since 2012. "To my knowledge the database was kept within a small group of Russians," a member of Leaked Source told Vice Motherboard.

Then LinkedIn's Stock Price Increased

LinkedIn has hardly been transparent about what it knew and when. But as of now, the answer appears to have been: "Very little." And in the absence of definitive information about the breach back in 2012, the right thing to do would have been to lock every account and force password resets.

From a business perspective, organizations might try to avoid issuing password-reset notices, worrying that their brand will take a hit, or users will defect, thus sending their stock price plummeting. In fact, the news about LinkedIn's breach appears to have had the opposite effect.

For starters, the company's stock price increased after news broke this month that the breach was worse than expected, although it's unclear why. One theory for that rise was that large numbers users visiting LinkedIn users caused a spike in the company's advertising revenues, says Jeremi Gosney, CEO of consultancy Stricture, which provides password-cracking software, hardware and services, says via Twitter. "Another theory is automated trading platforms were seeing LinkedIn in the news a lot, so it thought 'buy!'"

#leakedin update: after wasting much the day on Friday, over the weekend we reached 156,302,827 / 177,500,189 (88%) cracked #passwords16

Users Don't Pick Good Passwords

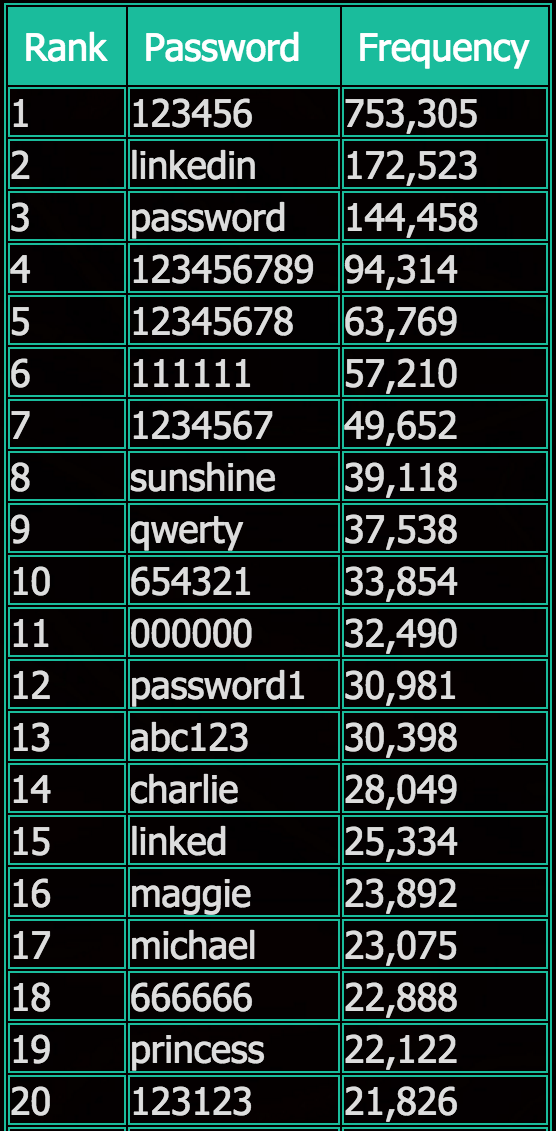

The leaked LinkedIn credentials have - once again - revealed that many users, left unchecked, pick "123456," "sunshine," "qwerty," "linked" and "princess" as their password. In fact, those were many of the choices LinkedIn users made in 2012, according to Leaked Source's analysis of hashed passwords that it cracked (see Why Are We So Stupid About Passwords?). And LinkedIn allowed users to select those poor passwords.

Top 20 password picks of 2012 LinkedIn users. (Source: Leaked Source)

Top 20 password picks of 2012 LinkedIn users. (Source: Leaked Source)Of course many security experts have long advised users to not reuse passwords across sites and to only pick long and strong passwords. And debate rages over whether users should reset their passwords on any site that ever suffers a breach - since it may portend worse - or else wait for related warnings from the breached organization.

But whatever passwords users might have picked, the LinkedIn breach is a reminder that unless passwords are securely stored, and hashed using secure techniques, it's child's play to crack them. LinkedIn, for example, was using the SHA1 cryptographic hash function, which security experts have long warned is not a secure way to hash passwords.

"People still make bad password choices," says Australian security expert Troy Hunt in a blog post.

"For me, what was more interesting about the whole thing was to witness both how the data was spreading and how comprehensively the weak cryptographic storage was being cracked," says Hunt, who runs the free "Have I Been Pwned?" breach-notification site - which sends alerts to email addresses registered with the site, when those email addresses show up in public data dumps.

At Least We Know About This One

Hunt says he's been fielding a lot of questions over why the stolen LinkedIn data took four years to come to light - and it's not clear why - or what attackers might been doing with it in the interim.

But he notes that the full extent of the LinkedIn breach taking four years to become known highlights how breaches may be much worse than they first appear. And it's also a reminder that "there's a lot of hacked companies we don't even know about," he says, and which may take years to come to light.