Anti-Malware , Encryption , Risk Management

Numerous Cisco Devices Still Vulnerable to EXTRABACON Cisco Patched Equation Group Exploit, But Uptake Lags, Rapid7 Warns Cisco ASA 5540 Adaptive Security Appliance. Photo: Dave Habben (Flickr/CC)

Cisco ASA 5540 Adaptive Security Appliance. Photo: Dave Habben (Flickr/CC)Tens of thousands of Cisco Adaptive Security Appliances remain vulnerable to a powerful exploit that many security experts believe was created by the U.S. National Security Agency, according to scans conducted by security firm Rapid7 (see Cisco Patches ASA Devices Against EXTRABACON).

See Also: From Authentication to Advanced Attack Vectors: Top Trends in Cybercrime in Q1 2016

The zero-day exploit, called EXTRABACON, dates from 2013 and appears to have been developed by an organization called the Equation Group, which is widely believed to be associated with the NSA's Tailored Access Operations team (see NSA Pwned Cisco VPNs for 11 Years).

The exploit was released as part of an Aug. 13 attack-tool dump from a group calling itself the Shadow Brokers. The attack exploits a vulnerability in Cisco ASA firmware code that could allow a hacker to remotely gain full control of the device. Cisco ASA network security appliances provide anti-virus, firewall, intrusion prevention and virtual private network capabilities, and the flaw could be used to decrypt any traffic encrypted by the VPN.

Security experts say the vulnerability isn't easy to exploit, but does enable an attacker to bypass Cisco ASA device authentication, and thus could be attractive not just to intelligence agencies, but also cybercrime groups, including botnet builders.

Not all Cisco ASA devices can be exploited using the flaw. "The requirements for the ExtraBacon exploit are that you have SNMP read access to the firewall, as well as access to either telnet or SSH," according to security researcher XORcat, who confirmed that Cisco ASA devices running up to firmware 8.4(4) were at risk. Subsequently, however, Hungarian security firm SilentSignal said that it had been able to modify the exploit to work on any ASA device, including version 9.2(4).

We successfully ported EXTRABACON to ASA 9.2(4) #ShadowBrokers #Cisco pic.twitter.com/UPG6yq9Km2

Cisco says there are more than 1 million ASA devices deployed around the world.

Counting Vulnerable ASA Devices

Security researchers at Rapid7 decided to see how many unpatched Cisco ASA devices they could find. Rapid7's Derek Abdine and Bob Rudis say in a blog post that the company's in-house internet scanning project, dubbed Project Sonar, recently counted more than 50,000 Cisco ASA devices that were configured to act as SSL VPNs (see Scans Confirm: The Internet is a Dump).

But they wanted to know how many might be vulnerable to the vulnerabilities revealed by EXTRABACON, which generally require SNMP and telnet/SSH access to a vulnerable device to be enabled, before the exploit can be deployed.

Related efforts, however, were constrained in part by legal concerns. "Actually testing for SNMP and telnet/SSH access would have let us identify truly vulnerable systems," they say, but laws in the United States and elsewhere prohibit anyone from making "credentialed scan attempts" on devices they don't own. Instead, the researchers used hping to query device uptime. Specifically, the researchers counted how many machines had been rebooted since Cisco began releasing patched ASA firmware on Aug. 15, and since SilentSignal released its Aug. 25 blog post warning that they'd been able to update the Equation Group attack to exploit all current ASA devices.

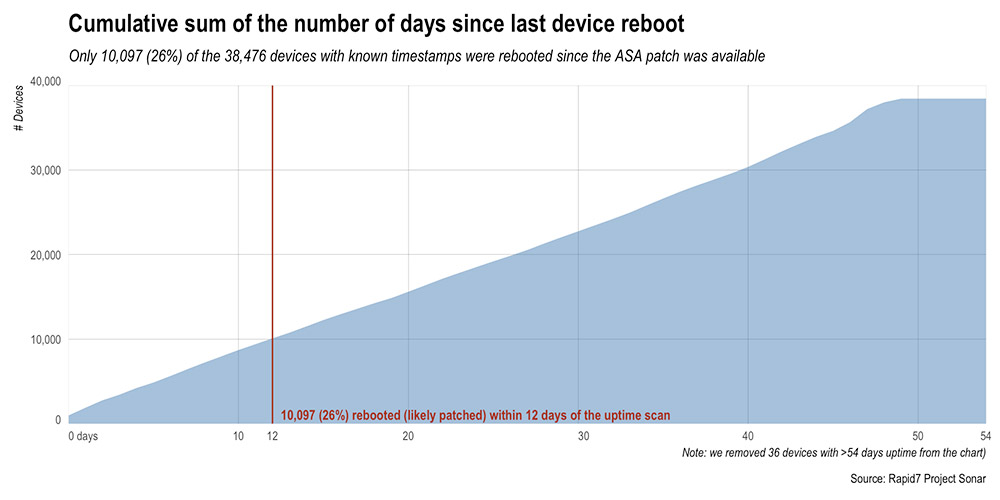

Of the 50,000 Cisco ASA devices configured to be SSL VPNs that were identified by Rapid7, about 12,000 prevented them from capturing timestamps via hping. That left 38,476 systems, and of those, only 10,097 had been rebooted since Aug. 26, suggesting that they might have been patched.

In other words, the scans found at least 28,000 unpatched ASA devices.

Examples of presumed-vulnerable organizations include an unnamed large Japanese telecommunications provider with 55 devices, a large U.S. multinational technology company with 23 devices and a large U.S. healthcare provide with 20 devices.

"This bird's eye view of how organizations have reacted to the initial and updated EXTRABACON exploit releases shows that some appear to have assessed the issue as serious enough to react quickly while others have moved a bit more cautiously," the researchers say. "It's important to stress, once again, that attackers need to have far more than external SSL access to exploit these systems. However, also note that the vulnerability is very real and impacts a wide array of Cisco devices beyond these SSL VPNs."

The number of detected Cisco ASA devices that have been rebooted - and thus theoretically patched - following EXTRABACON-related warnings. Source: Rapid7

The number of detected Cisco ASA devices that have been rebooted - and thus theoretically patched - following EXTRABACON-related warnings. Source: Rapid7

Patch Sooner, Not Later

The Rapid7 researchers say their study is a reminder to enterprise IT departments to ensure that they have an up-to-date inventory of deployed devices and firmware versions, that they patch Cisco ASA devices sooner than later, and until then ensure such devices aren't sitting ducks (see How to Cope With Intelligence Agency Exploits).

"EXTRABACON is a pretty critical vulnerability in a core network security infrastructure device and Cisco patches are generally quick and safe to deploy, so it would be prudent for most organizations to deploy the patch as soon as they can obtain and test it," the researchers say.

It's unlikely, however, that all vulnerable Cisco ASA devices will see patches get installed. Indeed, unpatched devices and operating systems never seem to die, instead just gradually fading away while never quite reaching extinction.

In June, for example, security researcher Billy Rios told me that more than 200,000 internet-connected systems remained vulnerable to the OpenSSL vulnerability known as Heartbleed. That was a decrease from an April 2014 high of 1.5 million vulnerable devices, which fell to 250,000 vulnerable devices in January 2015. But more than two years after Heartbleed was found, it remained far from extinct.