Data Breach , Fraud , Insider Fraud

Mega Leak Reveals Alleged Money Laundering, Tax Avoidance, Sanctions Dodging

Security experts worldwide are sorting through the implications of what's being called the "Panama Papers" leak. The 11.5 million leaked documents highlight an elaborate web of offshore holdings that everyone from heads of state and politicians to celebrities and fraudsters have allegedly used to hide billions of dollars. It's not yet clear, however, who leaked the massive amount of information or how the leaker obtained the data.

See Also: Proactive Malware Hunting

The documents show that offshore shell companies have apparently been used to disguise money laundering, tax avoidance and sanctions-dodging schemes, according to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. The shell companies allegedly have ties to everyone from drug barons and leaders of rogue nations to fraudsters and current and former heads of state.

The April 3 release of the Panama Papers was spearheaded by Süddeutsche Zeitung, which received a 2.6-terabyte data set from an anonymous source. The newspaper shared the data with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which released a trove of related data. Over the past year, it says, 400 journalists from more than 100 news media organizations in 80 countries have been poring over and authenticating the information.

The leaked data originated from Mossack Fonseca & Co., a Panama-based law firm that has more than 40 offices worldwide, including in the Bahamas, China, Columbia, Israel, the Netherlands, Singapore, Thailand and the United Kingdom, according to Gerard Ryle, ICIJ's director. The leaked records cover the period from the firm's founding in 1977 until the spring of 2016, and list almost 15,600 shell companies created by the firm to help clients mask their financial affairs, according to the investigative reports.

The leak reveals how the shell companies have been used to launder extensive amounts of money, including $2 billion that's been tied to banks and shadow companies linked to associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to an analysis published by the ICIJ.

Overall, the leak includes 4.8 million emails, 3 million databases, 2.2 million PDFs, 1.1 million images and 320,000 text documents, among other information. At least 12 current or former heads of state - and at least 60 individuals who have links to current or former world leaders - are named in the data, BBC reports.

"The leak will prove to be probably the biggest blow the offshore world has ever taken because of the extent of the documents," Ryle tells BBC. Meanwhile, French President Francois Hollande hailed the leak, saying it would help his government "increase tax revenues from those who commit fraud."

Mossack Fonseca didn't respond to a request for comment on those allegations. But the company has released a statement characterizing any suggestion that it helped individuals create corporate entities designed to disguise their identities as being "completely unsupported and false."

Leak From Anonymous Source

The story of the leak began at the end of 2014, when Süddeutsche Zeitung says it was approached by an anonymous source who offered reporters data. "I want to make these crimes public," the source said, adding that all communication would only take place via encrypted channels, and that there would never be any in-person meetings. "My life is in danger," the source told the newspaper. The newspaper says that it still does not know the leaker's identity.

The leaked data included encrypted, internal documents from Mossack Fonseca, which allegedly demonstrate how the firm helped individuals sold shell companies that could be used to disguise business activities and owners.

Of course, offshore accounts are not necessarily illegal. Indeed, numerous corporate entities - ranging from Google to the Irish rock band U2 - use them to avoid paying taxes in certain countries. "Generally speaking, owning an offshore company is not illegal in itself. In fact, establishing an offshore company can be seen as a logical step for a broad range of business transactions," Süddeutsche Zeitung reports. "However, a look through the Panama Papers very quickly reveals that concealing the identities of the true company owners was the primary aim in the vast majority of cases."

Revealing the true identities of the owners of various corporate entities has already begun triggering related questions, for example, about the transparency and accountability of the more than 125 politicians and public officials named in the leaks. Already, Iceland Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson has faced calls to resign after the leaked information apparently showed that he had an undeclared interest in a shell company called Wintris that he created - with his wife - via Mossack Fonseca, and used to invest millions of dollars of inherited money. In response to related questions in recent weeks, Gunnlaugsson transferred sole ownership of the company to his wife, ICIJ reports. On April 4, he reportedly refused to resign.

A Massive Amount of Data

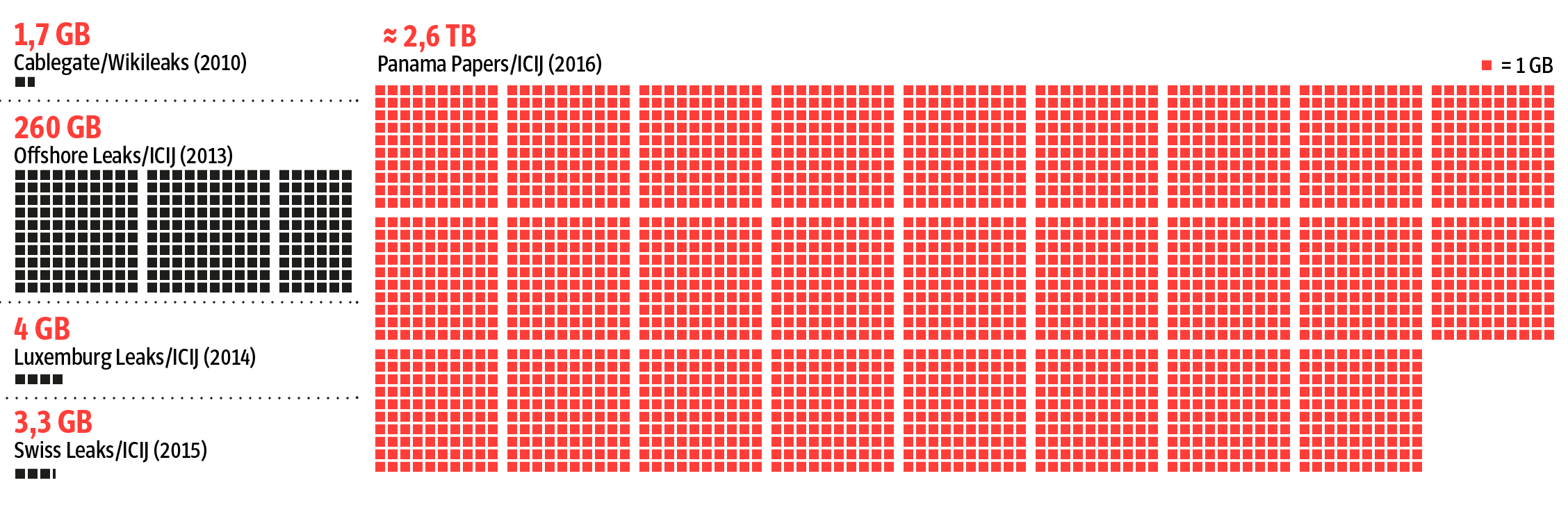

How the Panama Papers leak compares with previous leaks. Source: Süddeutsche Zeitung.

How the Panama Papers leak compares with previous leaks. Source: Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Banks Highlight Recent Improvements

Banks named in the documents as referring clients to Mossack Fonseca to set up shell companies for the purposes of tax avoidance include Commerzbank, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Société Générale and UBS. Some of those banks have now defended their business practices and more recent, related safeguards.

For example, UBS tells ICIJ that it knows the identities of all of its clients and enforces strict rules against money laundering. Credit Suisse and Société Générale say they enforce counter-fraud and anti-money-laundering rules, and Credit Suisse says that since 2013 it has required private clients to prove their compliance with tax regulations. Deutsche Bank has highlighted its November 2015 agreement with the U.S. Justice Department, including a fine of $31 million, over the bank's use of Swiss bank accounts to help U.S. residents evade taxes. HSBC spokesman Rob Sherman tells the ICIJ: "The allegations are historical, in some cases dating back 20 years, predating our significant, well-publicized reforms implemented over the last few years."

Mossack Fonseca, meanwhile, has downplayed the leaks and threatened to sue any organization that reports on any information contained therein. In a statement, the firm says that it is a "responsible member of the global financial and business community," that it "regrets" any misuse of its services and is threatening "to pursue all available criminal and civil remedies" against news organizations that "have had unauthorized access to proprietary documents and information taken from our company and have presented and interpreted them out of context."

Mossack Fonseca was the focus of a 2014 expose by Vice Magazine, which said the firm was one of multiple organizations known for setting up shell companies used by "oligarchs, money launderers, and dictators."

"While the so-called 'Panama Papers' focus a lot of attention on Panama, it's important to not miss the connections to the U.S., where Mossack Fonseca - the Panamanian firm - has affiliated offices engaged in similar business," says Clark Gascoigne, interim executive director of the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency Coalition, a U.S. not-for-profit organization, in a statement. He has called on Congress to close such loopholes.

Leak Analysis: Ongoing

Given the quantity of data involved in the release, security experts say that new insights will undoubtedly come to light as reporters and researchers further review the information. Already, however, some of the released data highlights activities that might not be illegal, but which appear to be at least legally questionable.

For example, the Guardian reports that the father of British Prime Minister David Cameron "ran an offshore fund that avoided ever having to pay tax in Britain by hiring a small army of Bahamas residents - including a part-time bishop - to sign its paperwork." Ian Cameron, who died in 2010, was reportedly one of five U.K.-based directors of the fund, which allegedly sought to evade U.K. taxes on behalf of wealthy U.K. residents, by incorporating the fund in Panama.

How prevalent is the use of offshore accounts to hide funds? That question is impossible to precisely answer. But according to University of California at Berkeley economics professor Gabriel Zucman, reports Vice, at least 8 percent of the world's wealth - totaling $7.6 trillion or more - is hidden in offshore tax havens.