Beware malicious printer drivers. (Source: Vectra Networks)

Beware malicious printer drivers. (Source: Vectra Networks)On July 12, Microsoft issued a patch (MS16-087) that shows the dangerous trade-off sometimes made between security and convenience. It's an attack so devilishly smooth that it's a wonder hackers had not figured it out before.

See Also: From Authentication to Advanced Attack Vectors: Top Trends in Cybercrime in Q1 2016

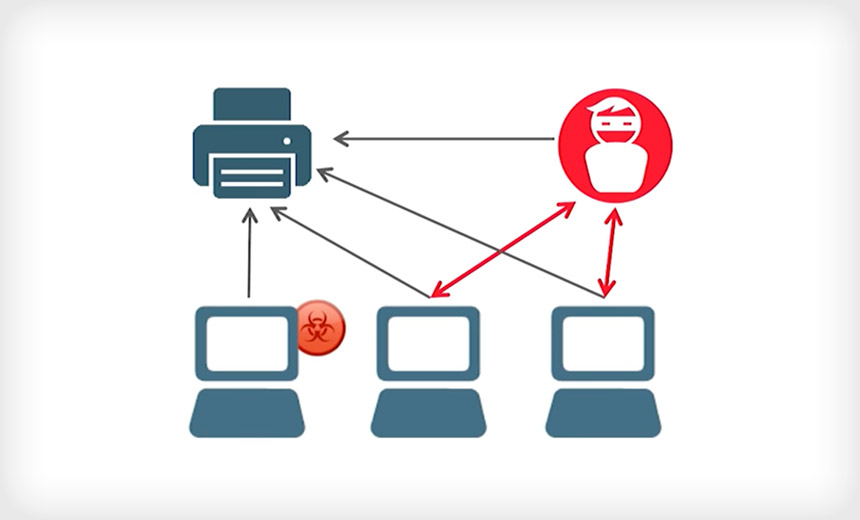

The finding comes from Vectra Networks, which decided to test if it was possible to deliver malware from a nearby printer to a Windows machine. The attack relies on a protocol called Microsoft Web Point-and-Print, which the company incorporated into Windows to make it easy to connect to a printer.

It's impractical for administrators to have to install a variety of printer drivers for every machine they manage. The Microsoft Web Point-and-Print protocol, introduced around 2007, is designed to deliver a driver for whatever printer that is nearby.

A printer driver is given a free pass: it's not subject to User Account Control, or UAC, which warns users before installing new software. That was a decision by Microsoft to make the process of getting ready to print easier. Also, a driver's digital signature - used to verify if software is legitimate - isn't checked. The driver gets installed straight away with high privileges at the system level.

To test the theory, Vectra Networks found a bug in printer software that allowed them to insert malicious code into a driver. In a demo video, Vectra shows the malicious driver was accepted by the Windows machine and granted the attacker a command-line shell. What's worse, even if the malware is removed, any time a user is close to the same printer, it would be delivered seamlessly again. Vectra says it turned the printer into "internal drive-by exploit kit."

The driver issue is less of a coding mistake than a design or logic bug, says Nicolas Beauchesne, senior security researcher with Vectra. It probably escaped attention sooner because there are fewer tools to detect logic bugs compared to implementation flaws, he says.

"As we improve prevention technology and logic analysis tools, we might expect to find that there are many more logic bugs then we expected, and we may also find that these have been lurking for years," Beauchesne says.

And it may have not been such a secret. "I believe that if a security vendor can think about this angle and find an exploit, an attacker would have thought about it before as well," says Chris Goettl, a program product manager for LANDESK Software.

Long-Term Problem?

Vectra Networks is reverse engineering Microsoft's patch to figure out if this kind of attack will be a long-term problem. But the fix also depends, in part, on the cooperation of printer manufacturers.

"Microsoft is pretty much between a rock and a hard place," Beauchesne says. "Printer vendors have yet to agree on a printing standard or, in some cases, to even sign their drivers. Ensuring that every driver is signed would break older printers until their respective vendors deploy new drivers for all their models."

There are a couple of small barriers to this kind of attack. In Vectra's first example, attackers would have to find a vulnerability in printer software in order to insert malicious code. That's not terribly difficult, however. They would also have to tamper with a printer that is already inside an organization or spoof a device that appears on the network to be a printer, which would also require inside access.

But Vectra found a much more dangerous possibility: an attack delivered over the web. That style of attack could deliver a malicious driver through a compromised web page or even a malicious advertisement. A web attack could be executed using either Web Point-and-Print or the Internet Printing Protocol, which is a set of standards for printing first developed by Novell and Xerox in 1996.

There is a saving grace: Aside from Microsoft's fix, it's possible to control Web Point-and-Print through group policy settings, including just simply turning it off. That would probably irritate users, but at minimum, it would prevent this style of attack. Pick your poison: a gander of users who can't print from some obscure early 2000s printer in the basement, or explaining to the CIO why data has gone walkabout.