Latest News

Speech by Charles Randell, chair, FCA, delivered at the retail Banking Conference 2019 in London.

But if there’s a remake of 'It’s a Wonderful Life', the plot needs to change. Today’s issue isn’t banks coming to town, it’s banks leaving town.

The picture in Burslem

A couple of weeks ago I visited Burslem, a town of 22,000 people, one of the 6 that make up Stoke-on-Trent. It’s the mother town of the Potteries, once home to Royal Doulton and Wedgwood, and home to many magnificent examples of Victorian civic architecture.

Burslem’s also been in the news as the first town of its size to have no bank branch and no free-to-use ATMs. 3 banks have closed their branches and the nearest ATM to the town centre charges 95p for withdrawals. The local MP, Ruth Smeeth, took me round to show me the impact that the lack of free access to cash has on her constituents.

Burslem’s a beautiful town, but it’s one with economic challenges. Local manufacturing jobs have dwindled. It’s a low wage and low income area, on average. Food bank and high cost credit usage - legal and illegal - spike during the school holidays when free school meals aren’t available. We know that people on lower incomes are disproportionately high users of cash, partly because they find it useful to budget with cash: you can’t spend what isn’t in your wallet. Now that Universal Credit is paid directly into bank accounts - which may result in fewer people being completely unbanked - it does mean that to budget in this way you have to take cash out.

So there’s a big cash economy in Burslem, in the pubs, hairdressers, cafes and takeaways. At the twice yearly Burslem fair, which funds local charitable activities. At the Swan Bank Church, which is one of the other ties binding this community together.

LINK, the ATM operator network, uses a radius of 1 kilometre from the nearest free-to-use cashpoint to assess whether ATM operators should receive additional premiums for keeping ATMs open. And on a map, viewed in our office or in a bank’s headquarters in London, it looks like there’s a free-to-use ATM within 1 kilometre of Burslem town centre. But once you’ve walked past the one at the McColl’s store on the way in from Longport station, you realise there’s a steep hill up to town. If your mobility is impaired, if you’re elderly or pushing a buggy, it could be impossible to make the trip. And if you’re in Burslem enjoying the nightlife on which the town centre depends, it’s a long round trip to a free-to-use ATM. Of course, at night the only place in the town centre where you can take money out without a fee - the Post Office counter - is closed. And in the daytime there can be long queues and not much privacy in the Post Office.

The view from a distance

Viewed from a distance, the big picture doesn’t look too bad. Yes, the number of bank branches has decreased dramatically in the last 5 or 6 years - between 2012 and 2017, the UK lost over 3,000, or nearly a quarter of its bank and building society branches. But when the FCA’s Strategic Review of Retail Banking Business Models looked into the impact of branch closures, it found that, region by region, branch closures have been fairly evenly spread. Where branches do close, we found a compensating increase in mobile banking, and a drop in usage of nearby potential substitute branches, showing that people often do find alternative ways to access banking services. And there’s a voluntary best practice code, operated by the Lending Standards Board, that aims to manage the impact of branch closures on affected areas.

There are also a lot of free-to-use ATMs. Although the numbers have started to decline, at the end of 2017 there were more free-to-use ATMs in the UK than ever before - nearly 55,000 - and 97% of cash withdrawals are made without a cost to the consumer. And this despite a steep and continuing decline in the demand for cash from ATMs. For the first 2 months of 2019, weekly transaction volumes have fallen by an average of 8.4% against the same week last year. In January 2019, £500 million less was withdrawn from the LINK ATM network compared to January 2018.

People may not be using as much cash, but they are interacting with their money more than ever before. UK Finance estimates that in 2017 38 million people, or 71% of adults, used online banking, and there were 5.5 billion log-ins to banking apps. There are more ways to access services, like applying for a mortgage or personal loan, that used to have to be done face to face in a branch. And there are more ways to pay than ever before - contactless cards, digital wallets, mobile payments, faster payments. As the use of cash has declined overall, and the cost of accepting smaller card payments has decreased relative to handling cash, some businesses and retailers are deciding to go completely cashless.

The 'poverty premium'

But this wonderful life of online banking and mobile payments is cold comfort if you can’t do any of these things.

Cash payments still make up around a third of all payments in the UK, and around 2.2 million people say they use cash for all their day-to-day transactions. Many of these people are on low incomes. Our Strategic Review of Retail Banking found that local authority areas with more branch closures have slightly higher rates of unemployment on average, and higher proportions of people living in deprivation.

So having to pay to access cash disproportionately affects those who are least able to afford it. I recently saw the poverty premium in action when I visited a project supporting mothers and their children who live in insecure accommodation, and who depend on statutory payments from the local authority to get by. But the local authority does this by issuing them with prepaid cards which charge a minimum of £1 and up to £3.75 for cash withdrawals, meaning that a high percentage of the money the mums need is taken away again.

Cash is also disproportionately used by older people. Where branches close, we don’t see any increase in mobile banking among the over 60s. So while most people adapt to alternative technology, there are some who need a lot more help to do so. And whether you’re old or young, if you’re poor, online banking means access to a computer or paying for data on your phone. Issues people in this room probably don’t have to think about.

Of course bank branch closures can hit rural areas particularly hard. In rural areas only around 50% of consumers live within 5 miles of their nearest branch, compared to 90% in urban areas.

And without local branches to deposit cash, it’s costing businesses and charities more to accept it, to transport it, to deposit it, and it increases their risk of being robbed. So branch closures are impacting retailers and other small businesses.

The Post Office

One idea that’s often mooted as a solution to these issues is the Post Office. Indeed, one of the criteria which LINK use for assessing whether a remote ATM needs to be replaced is whether there is a Post Office nearby with reasonable opening hours that could provide a substitute. The CEO of financial services and telecoms at the Post Office spoke at a recent Treasury Committee hearing about how managers of departing branches literally hold the hands of vulnerable customers as they are introduced to postmasters and told how their banking needs will now be met.

But while the Post Office’s Banking Framework has expanded its ability to offer cash withdrawals and deposits, it doesn’t have a universal service obligation for its banking services. The increasing costs of cash handling means that its banking business is not profitable, and to offer a full bank branch service would require huge investment from central government. Users also report slower cash and cheque clearing at Post Offices compared to banks.

The current role of regulation

You may ask why we need to discuss this at all when there are already several regulators with responsibilities for cash and payment systems - the FCA, the Payment Systems Regulator and the Bank of England.

I don’t believe we need more regulators but we do need to discuss their roles. The regulators haven’t taken on the role of compelling a bank to keep the last branch in town open. If we did, there would be an even stronger incentive for banks to close branches they deemed unprofitable as quickly as possible, to avoid being the last bank in town. So we would need a fair system for recognising the costs of staying open which are borne by the last bank and deciding who should bear those costs and whether and how the bank should receive a reasonable return on its capital.

A lot of thought would also need to be given in designing a system for a national regulator to make good individual decisions about what access to cash or branches people in Burslem or any other individual local community should have. Every community is different, so this has to be a decision involving local people, even if it will be challenging to weigh up the strength of local community feeling against the high costs of maintaining the necessary infrastructure.

For comparison, we might look at telephone boxes. Their usage has almost flatlined since the rise of mobile phones. But, if you’re out of battery, or if you don’t own a mobile phone, or if you’re somewhere with no signal and you really have to make a call, maybe a 999 call, they might still be your only option. Maintaining them comes at a cost, estimated at £6 million a year in 2017. But BT has a universal service obligation to provide a reasonable network of phone boxes, and OfCom rules offer local communities a veto - funded by the industry - if BT wants to remove the one and only phone box on a site.

The Post Office has a similar commitment to consult with local communities in the event of a branch closure as part of its commitment to maintain the size and accessibility of the Post Office network.

There is no universal service obligation for cash or banking. As I’ve mentioned, there is a process for consulting the local community about branch closures through the voluntary Access to Banking code. However, some people have suggested that the criteria for defining what makes a branch ‘regularly used’ to make these decisions are unreasonable and differ starkly between banks, and that stricter geographic criteria should be used. It’s also telling that the House of Lords Committee on Financial Exclusion found that no decision to close a branch had ever been reversed as part of this process.

With ATMs, there’s a stronger set of safeguards. LINK has made commitments to maintain the broad geographic spread of ATMs and specific commitments to maintain an estate of protected ATMs based on a test that there should be an alternative free-to-use ATM or suitable Post Office within 1 kilometre. LINK does this by increasing the payments to the operator of the ATM machine. Which, at present, is up to £2.75 per withdrawal or, in the most extreme cases, LINK paying an operator to manage a machine directly on its behalf. These interventions are paid for by LINK’s members, and passed on to their customers. The good news is that we’re now seeing examples of this process working to restore protected ATMs that have closed.

But it’s a challenging task for LINK to make decisions which recognise all the local realities which mean that, for example, an ATM some distance from a town centre like Burslem may not serve a community’s needs, taking into account wider social issues and local context like broadband speeds, population profile and access to social care, and public transport.

Access to Cash Review and the long-term strategy

It’s in light of these issues that I welcome Natalie Ceeney’s Access to Cash Review, whose final report was published last week.

As the use of cash declines, there are big questions to be asked. We’ve grown used to access to cash being free. But of course someone has to pay for it. Aside from the cost of banknote and coin production, a complex infrastructure of cash centres, depots and transportation exists to allow cash to be in the right place. The Access to Cash Review estimates that this costs £2 billion annually. Many of these costs are fixed, and most are borne in the first instance by a concentrated group of private companies. The Review also suggests that there is no guarantee any other competitor would step in should one of the infrastructure providers leave the market. So I also welcome the Bank of England’s commitment to bring together industry and regulators to work out how we can reform the UK’s wholesale cash infrastructure to make it more efficient and cost effective for everyone.

Assuming the UK’s wholesale cash infrastructure can be made more efficient and cost effective, the system will come under increasing pressure over the next few years as fewer and fewer people use cash. The cost per transaction is likely to rise, even if the service is free to the person using the ATM. In any event, more and more small retailers, operating on wafer thin margins, could refuse to accept cash. Even if there were a universal service obligation on LINK or the banks, its costs would be passed on by the industry and ultimately borne by consumers, and it still wouldn’t make it economic or reasonable for all retailers to accept cash.

So the declining use of cash plays into a much broader debate about financial inclusion which includes the future of communities in a digital age, the way a range of public services are delivered and consumer education. We need to discuss not just who should pay for the cash system, but also what action government and local authorities should take to support people to adapt to a world where cash may not be accepted. And in the meantime, whether we should see cash as a public good, part of a fair society as well as a back up payment system if IT systems fail, the cost of which should be socialised; or whether the cost of cash should be borne by the (sometimes vulnerable) people who continue to use it.

LINK has committed to maintain the broad geographic spread of free-to-use ATMs, but we may need to go further to serve the cash needs of communities: looking at increasing the number of ATMs which accept cash deposits as well as withdrawals, and other ways of keeping down the costs of local cash handling, such as cashback offered by retailers.

And if the banking sector is currently providing a service to a community through branches that we want to maintain, who should pay for this when the last bank in town wants to close its branch? Is it reasonable to expect the Post Office to pick up the baton when its funding model, staff training, branch facilities and statutory backing are designed for postal services, not banking? Are there other models, such as shared branches, community banks, credit unions or local authority supported banking centres which can help to ease the impact of the reduction in bank branches?

Conclusion

The time to face up to these issues is now. Bank branch closures are already a fact, and so is the reducing use of cash. The Access to Cash Review concludes that we might have 15 years before cash transactions fall to just 1 in every 10. But we simply don’t know for certain how quickly online banking services will develop and how quickly more people will choose to use less cash.

So it’s right that we plan for a range of future outcomes, and that there’s a broad social debate about financial inclusion in a digital age.

Mobile banking, cashless transactions and a range of other technological developments may mean a wonderful life for some people. But we mustn’t forget that for some time to come, others will need access to cash or bank branches. The FCA and the Payment Systems Regulator have both highlighted these issues. We welcome the publication of the Access to Cash Review and are ready to play our part in this important discussion.

Like me, you may have come across people who appear obsessed with security but happily book cabs, order food, and even make payments on their mobile phones without entering a single password / PIN.

This is not as contradictory as it seems if you look at the end-to-end customer journey.

It just means that people value security when they're in the awareness or TOFU (top of funnel) stage of the funnel but they want convenience after reaching the repeat purchase or BOFU (bottom of funnel) stage of the funnel.

For the uninitiated, Customer Journey can be defined as the path taken by customers while interacting with a company / brand. A customer journey traverses multiple stages in a customer’s relationship with a brand viz. awareness, interest, desire, action, repeat purchase and advocacy.

In plain English, the above observation means that people will switch from cash to a digital payment product only if they're convinced it's secure but also that, having started using the product, they'll use it regularly only if it's easy to use.

In payments (and in many other products and services), studies have shown that consumers have different considerations at different stages of their purchase journey and that all considerations are not created equal.

Many payment service providers (PSP) don't get this cardinal trait of consumer behavior and solve only for the TOFU driver, namely, security. Not surprisingly, they struggle to gain mainstream adoption.

Take, for example, two factor authentication. When Reserve Bank of India mandated 2FA for all online payments in India, it presumably thought "people want security, 2FA provides security, ergo people will flock to online payments".

What happened was exactly the opposite. Although the central bank-cum-banking regulator's move was well-intentioned, 2FA caused tremendous friction and resulted in an alarmingly high rate of failed payments for reasons explained in the following exhibit.

People like me who were paying for online shopping with credit cards for years switched to cash on delivery. Many others never tried online payments for online shopping. COD Still Rules Ecommerce In India with a 60% share.

When there was a cash crunch in the wake of the de/remonetization of high value currency notes in India in November 2016, people didn't switch from COD to digital payments – they simply stopped shopping online because they didn’t have enough cash to pay on delivery.

PSPs that have required explicit 2FA for each and every payment – “according to RBI mandate” – have flopped. On the other hand, fintechs like PayTM provided a clever way to circumvent 2FA – or at least make it implicit – and became unicorns and household names in the process.

Let's look at another market: USA. While many security technologies were invented in the USA, not many of them have been implemented there. Let's take 2FA and EMV as examples:

The American regulator FFIEC mandated 2FA for online payments in 2005 and reissued its guidelines in 2012. But online payments don't require 2FA in USA even today. Stripe, the leading payment gateway company, at one time minced no words about its dislike for 3D Secure, the go-to method for implementing 2FA for online payments. Its website once noted: "At Stripe we've so far opted not to support 3D Secure since we believe the costs outweigh the benefits." The EMV migration deadline has come and gone over a year ago in USA, still fewer than one-third of US retailers have implemented Chip and PIN technologies.

(https://twitter.com/s_ketharaman/status/795966887565938688)

The sky hasn't fallen.

Sure, there have been a number of data breaches in the US e.g. Experian, Target. But they have all happened on the server side. And it looks like the country is fighting back with overwhelming force. According to New York Times, banks and card networks are adopting military-style tactics to fight cybercrime. If you're an optimist, these measures will convince you that Wall Street would be immune to such breaches. If you're a skeptic, then, fact is, these breaches can’t be prevented, no matter how many additional security-enhancing steps are put on the consumer-side.

The situation in Europe is a bit ambivalent. According to an article entitled EU Online-Security Plan Is Criticized in Wall Street Journal, "business groups are slamming a European Union proposal that would require customers to enter extra security information for online purchases. Credit-card companies and e-commerce associations worry that if online purchases become too cumbersome customers will abandon them." WSJ goes on to add that consumer advocates, on the other hand, say "there is no trade-off between antifraud protections and promoting e-commerce".

---

Security always wins when it comes to intent. Convenience always wins when it comes to action.

While PSPs must make all the right noises about security, it’s futile to anchor a digital payment product around security - an average user won't be able to jump through all the hoops required to make an app totally secure (no matter what s/he says before using the app).

I'm glad regulators and PSPs have learned this lesson. To paraphrase a famous quote from Steve Jobs, they've started taking the trouble to figure out what really appeals to customers instead of lazily giving consumers what they say they want. I also suspect they've been nudged in this direction after witnessing the runaway success enjoyed by products that have treated security more as a go-to-market message than core product feature.

(https://twitter.com/s_ketharaman/status/965564220552171521)

Here are a few results of the change in approach:

The Indian banking regulator has emphasized convenience over security in all recently launched digital payment products and services such as UPI, BHIM, Recurring Payments and Contactless Payments. (Considering that some of these apps directly touch bank accounts, I think the pendulum has swung a little too far to the other extreme, but that's perhaps a post for another day.)

(https://twitter.com/s_ketharaman/status/791618231169679360)

In the past, my go-to mobile payment app HDFC Bank PayZapp would log me out automatically after a few minutes of inactivity. This meant I had to enter a PIN to make the next payment. This was obviously a hangover from the shared desktop web security mindset. Recognizing that this approach is needlessly overconservative for a personalized device like a smartphone, PayZapp has modified its logout procedure lately: I now need to tap the Logout button and confirm that I really want to log out of PayZapp. Looks like PayZapp has understood the advantage of letting the user remain logged in to its app at all times - the approach pioneered, AFAIK, by PayTM, India's largest digital payment product. A business associate, franchising specialist Prashant Srivastava, tells me that the way of making NEFT, IMPS and RTGS payments on his bank's NetBanking portal has changed lately. For nearly two decades, this Top 3 private sector bank in India used to gate A2A payments with a bingo card and mobile OTP. Lately, I believe, both of those challenges - and the associated friction - have gone away. Now, you select a payee, enter an amount, press the submit button. And, poof, your money has gone!I'm sure these UX-enhancing features will give a big boost to digital payments in the times to come. I'm also optimistic that they won't cause an alarming increase in fraud. (Go #CashlessIndia!)

---

Some people have proposed Intelligent Friction as a tradeoff between security and convenience.

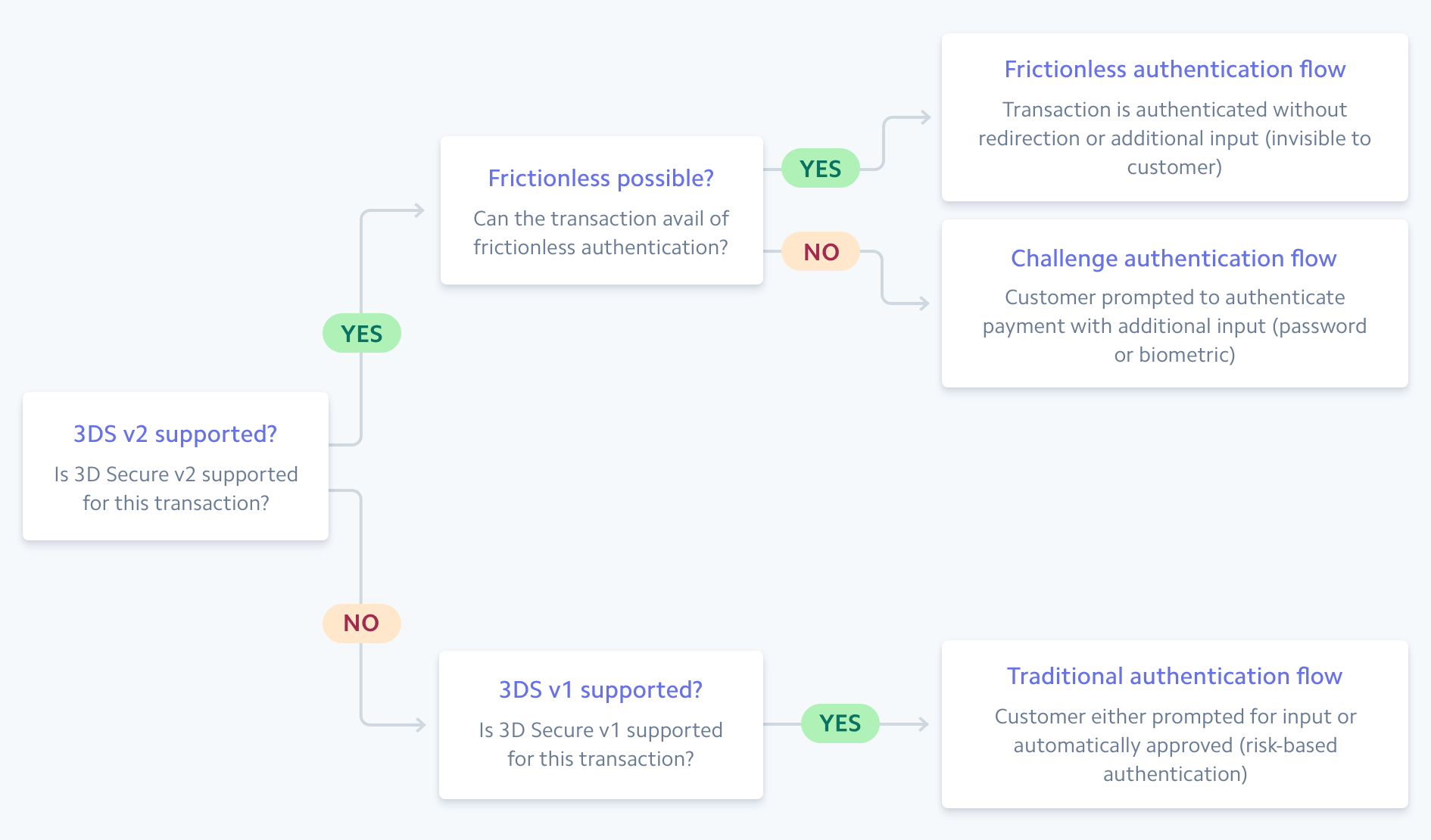

3D Secure v2 is one way to implement intelligent friction. Stripe, which had earlier panned 3DS v1, has a favorable opinion of 3DS v2.

3D Secure v2 (Image courtesy: STRIPE)

3D Secure v2 (Image courtesy: STRIPE)

But, if I were a merchant or a bank - or even a payor or PSP - I'd be cautious about anything that has the word "friction" in its name. The extra step(s) required to implement intelligent friction will inevitably delay the affected payments. Some of those payments may even fail if the extra moving part (e.g. mobile OTP) introduced in the "challenge path" is not reliable.

While consumers may keep retrying a delayed or failed payment on that one occasion, the anxiety and inconsistent user experience they go through will not only threaten conversion rates on that occasion but turn people off that mode of payment on future occasions - if not, gasp, drive them back to cash and cheques.

---

Buying and selling happens only when payments are successful. Business is lost when payments fail.

Convenience trumps security.

Winners know this and never let security screw up UX.

DISCLAIMER: If you've come this far, it should be obvious that this post is largely restricted to consumer-facing digital payment apps meant to be used by the average man on the street. By no means should security play second fiddle in the case of server-side applications and databases that store sensitive user and payments data and must be managed by trained professionals in such a way that they're fully secured from internal and external threats.

Deutsche Bank (China) Co., Ltd today announced that it has joined the NetsUnion Clearing Corporation’s network (NUCC) to facilitate the e-wallet payments of its corporate clients.

After joining the NUCC network, which links e-wallet providers with participating banks, Deutsche Bank will be able to offer faster and more efficient collection solutions, enhancing its corporate cash management offering.

Dirk Lubig, Head of Global Transaction Banking China and Head of Corporate Cash Management Greater China at Deutsche Bank, said: “We are proud to be one of the first foreign banks to join the NUCC platform. It is a step forward as we continue to expand our service offering in China. As non-banking payments record staggering growth, Deutsche Bank is well positioned to meet the e-commerce payment needs of its corporate clients onshore.”

A strong payments strategy is an advantage to any eCommerce industry, but none more so than the heavily regulated sports betting sector. As more and more bookmakers respond to growing consumer demand by shifting from land-based betting shops to online operations, the market grows increasingly competitive.

To gain an advantage over competition, operators focus on optimising the one direct consumer touchpoint available to them: the payment process. An integral feature of a strong payments strategy, the payment process must be engineered for ultimate consumer convenience.

The customer journey culminating at conversion on checkout is challenging by nature of the genre. In sports betting, transactions go both ways. Consumers expect ease and convenience, as well as security, when placing bets, but also in receiving their winnings. Any friction caused – in either direction – can result in poor conversion and/or retention.

Conversion by design

As the final potential stumbling block in the customer journey, the payment page itself must ensure that players follow through with their bet and complete their intended transaction. Not only must checkout be adapted to all possible devices, including desktop, mobile, and tablet, but it should also combine brand recognition, e.g. same colour scheme, font, theme, etc. as the merchant website, with a simple, intuitive user interface.

Equilibrium between conversion and security

In essence, all online bookmakers are attempting to find the ideal compromise between conversion and security. After all, heavy security measures risk alienating prospective players, while high conversion at the expense of limited security makes the operator a target for fraudulent activity. Any payments company will be able to offer a selection of both conversion-boosting products and risk management technologies, but it takes an experienced payment service provider to combine the efficiencies of both in order to achieve higher revenues for their client.

Communication is key

To establish reliability, any online merchant must enable effective communication with their target audience to resolve potential payment issues. Of course, their payment partner will be available to advise, but it is the operator’s responsibility to address customer complaints. In integrating a live chat on their website – or any other means of instant communication – merchants can settle disputes directly and protect against available losses.

As the conduit through which online bookmakers and gambling operators generate their profit, payments play a key strategic role. Investing time and resources into finding a reliable partner with whom to construct a comprehensive payments strategy will pay off in the long run, ensuring that merchants are best-placed to defend against potential risks, provide a convenient customer journey, and delicately balance targeted conversion with security.

ACI Worldwide, a leading global provider of real-time electronic payment and banking solutions, today announced an extension of its long-standing relationship with Capitec Bank, South Africa’s second largest retail bank. Capitec, a long-time ACI customer, now supports card and non-card payments acceptance through the UP Retail Payments solution – an integrated platform for all payment channels.

“We anticipate significant growth in transaction volume over the next ten years, as a variety of innovative digital payments products are launched - the combination of scalability and flexibility that ACI’s UP Retail Payments solution offers will not only support that growth, but also ensure we’re future-proofing our payments environment,” said Japie Britz, Systems Development Manager - Card Processing, Capitec Bank. “Transitioning to service-based architecture will reduce time-to-market and equip us to respond to global payments trends, enabling us to not only maintain, but expand our leadership position within South Africa’s financial services and banking sector.”

“Africa continues to be fertile ground for fintech and payments innovation, and South Africa - as the continent’s second largest economy - plays a key role,” said Manish Patel, vice president, ACI Worldwide. “Financial institutions need to move quickly to succeed in this challenging and dynamic environment, without compromising security and resilience of their core banking systems. Continuing its long-standing cooperation with ACI and use of Postilion, Capitec is strongly placed to grow its market share, leveraging more of our device and channel-agnostic payments technology as the needs of its customer base evolve.”

ACI supports core payment processing for Capitec with its enterprise-class UP Retail Payments solution, which is based on the Universal Payments (UP) Framework and built on open service-oriented architecture for robust payments orchestration. The solution, which delivers 24×7 secure payment capabilities and is currently used by 8 of the world’s top 10 banks, allows Capitec to create and expose payment services to external entities and to address PCI compliance requirements through tokenization.

OpenWay, a global leader in digital payment processing software, today announced the successful integration and compatibility of its WAY4 payment processing platform with the Gemalto SafeNet Payment Hardware Security Module (Luna EFT 2).

The Gemalto SafeNet Payment Hardware Security Module’s broad payment security functionality, flexibility and high-end physical and logical security architecture, along with PCI-HSM certification, makes it one of the most comprehensive encryption solutions on the market. It can be used for both in-house and cloud deployments of the WAY4 processing system.

Gemalto’s SafeNet Payment HSM also helps to ensure the security of payment processing environments for credit and debit cards, e-wallets, as well as online and mobile payment applications. To protect contactless mobile payments, it manages the entire cryptographic process from card enrollment and provisioning to tokenization and transaction processing. The solution specifically helps payment providers adhere to EMV security standards on both issuing and acquiring sides.

“As the growth of digital payments, specifically mobile payments, continues to accelerate, solutions that provide security, flexibility and cost savings will be in high demand. We believe that the SafeNet Luna EFT Payment HSM will provide WAY4 users with the scalability and flexibility they require when operating in the fast-moving digital payments market,” said Todd Moore, SVP Encryption Products at Gemalto.

“Seamless security of transactions is on top of mind for our customers. For many years OpenWay has been relying on the skills and expertise of the Gemalto’s payment security team, and now we’ve extended the range of compatible HSM devices with the SafeNet Luna Payment HSM. Our collaboration with Gemalto enables our customers to explore new business opportunities, such as online and mobile payments, in a more secure and cost-efficient way,” said Dmitry Yatskaer, CTO at OpenWay.

WAY4 is an open, omni-channel digital payment and card processing platform. It supports digital wallets, private label and branded card issuing, as well as merchant acquiring, financial switching and channel management. WAY4 is deployed by tier-1 banks and payment processors across the globe. OpenWay has a reputation for innovation, being one of the first in the world to support OEM-wallets, payment schemes tokenization, and the 3-D Secure 2.x protocol.

Gemalto and OpenWay solutions undergo regular audits to meet the requirements of PCI Security Standards Council (PCI-HSM and PA-DSS certificates respectively) and are certified by major international payment schemes.

PayPal is rolling out an Instant Transfer feature in the US, allowing consumers, and soon businesses, to instantly move money that they receive via the service into their bank accounts.

The move is part of PayPal's effort to make itself more attractive to new sectors, including gig economy workers - who are increasingly choosing the firm to get paid - by helping them get their hands on their money as quickly as possible.

The firm already offers an Instant Transfer to debit card option and has also targeted businesses with a Funds Now option that gives them access to money from completed sales within seconds.

Says COO Bil Ready in a blog: "Getting faster access to money is becoming more and more critical for most people, especially as the global workforce is evolving and an increase in less traditional and more entrepreneurial jobs means people have potentially less stable and more variable incomes."

"Faster access to your money can also mean being able to cover unexpected expenses and emergencies, staying on top of bills and avoiding late fees. For businesses, getting faster access to money from their sales can mean they can afford to hire more employees, purchase inventory, quickly invest back into their businesses and better manage their cashflow."

The new feature is made possible thanks to a partnership with JPMorgan Chase that gives PayPal access to The Clearing House's real time payments network.