Unfollow Me is a campaign from Broadly, highlighting the under-reported issue of stalking and domestic abuse, and amplifying the voices of victims and survivors. In the UK, we have partnered with anti-stalking charity Paladin's calls to introduce a Stalkers Register. Follow all of Broadly's coverage here.

For this piece, Motherboard partnered with Broadly to highlight When Spies Come Home, our extensive investigative series about the powerful surveillance software ordinary people use to spy on their loved ones.

When you think of “stalkerware,” what comes to mind is probably a spy-movie hacker planting chips on shoes or placing tiny video cameras on flies that hover around their targets. In reality, however, the stalkerware industry is much more mundane, and dangerous, than film tropes depict—especially for women.

Today, stalkerware—also called “spyware,” “consumer surveillance software,” or “spouseware”—takes the form of applications on or alterations to a device that enable someone to remotely monitor its activity. An application called PhoneSheriff, for instance, allowed its users to read texts and view photos on, as well as access the GPS location of, the phone on which it’s secretly installed.

As reported by Motherboard last year, tens of thousands of people fall prey to software and apps like PhoneSheriff, which was discontinued in March, 2018. And Motherboard’s analysis of a large cache of hacked files from Retina-X (the former maker of PhoneSheriff) and another spyware maker, FlexiSPY, revealed that those who utilize their products are most often ordinary people—such as “lawyers, teachers, construction workers, parents, jealous lovers”—not members of law enforcement.

There are at least dozens of consumer-level apps like PhoneSheriff on the market, with names like Mobistealth and Family Orbit. The FlexiSPY app is one particularly popular example of software marketed toward those trying to “catch” spouses or keep tabs on people without their knowledge: As Motherboard’s Joseph Cox reported in 2017, over the years, FlexiSPY has added features to send fake text messages, steal application passwords, take pictures remotely using a phone's camera, track web history, spy on Facebook, iMessage, and WhatsApp chats, and monitor aspects of Tinder usage.

There aren’t concrete numbers around how many people are victims of stalkerware abuse. But being surveilled by one’s partner is a reality for many who report abuse, and is a serious form of abuse itself, according to organizations like the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. In 2014, UK-based support network Refuge reported nearly 1,000 cases of victims needing help because they feared they were being surveilled, either through their personal devices or smart home technology like webcams and thermostats.

Fear, manipulation of self-esteem, isolation, and financial dependence are all part of the abuser’s playbook. Spyware and stalkerware tick several of these boxes: Having knowledge of someone’s whereabouts, connections, and conversations is invaluable for someone trying to control them.

Here are some things to know about how Stalkerware works and questions to ask yourself if you think someone may be tracking you.

How would stalkerware get on my phone in the first place?

Most of this software ends up on a device through one of two ways: A phishing attack (email or text links that contain viruses and trick you into clicking on them by pretending to be something/someone else), or physical access to the device.

In the first case, the abuser could send a link in an email that looks like they’re sharing an interesting website, but when clicked would actually trigger the installation of spyware onto your device without you knowing. The second requires the abuser to have access to the device’s passcode or PIN, which they could get from talking the victim into sharing it with them or by watching over their shoulder when they unlock the phone. They could also have bought the phone for them and installed apps before giving it to them as a gift.

Most of the apps someone would use to track someone via a device are framed as “remote access tools” to help parents or employers “manage” devices. But they’re easily used by people trying to control partners, instead.

How do I know if I have one of these applications on my phone?

"My number one tip for victims is to trust your instincts. If your instincts tell you that your ex or your current partner knows too much about you, it's entirely possible they're monitoring your activities," Cindy Southworth, executive vice president of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, told Motherboard in 2017.

This seeming sixth-sense about being stalked often doesn’t come from nowhere. Southworth gave the example that one woman’s ex sent her a link to shoes she had been looking at buying earlier, saying they would “look great on her.” This is the kind of manipulation and gaslighting that can keep a victim wondering if they’re making something out of nothing, or if the person they suspect is really watching them.

It’s difficult to tell if someone has installed stalkware on your phone, being that there’s typically no visible evidence. If you have an iPhone, however, it would likely need to be “jailbroken”—a process that removes manufacturer restrictions—in order for the installation to occur, since stalkerware is generally not available in the iPhone App Store. According to Motherboard reporter Joseph Cox, one possible way to tell if your phone has been jailbroken is to search your phone for an app called “Cydia,” which allows users to install software onto jailbroken devices. If the app shows us, this is a strong clue that someone may have been installing unwanted software onto your device. If it doesn’t, however, that’s not a guarantee that surveillance software isn’t already on your phone. You can bring your phone to a carrier like an Apple store to have them check it out, but even this is quite risky for someone potentially being watched.

I just realized I’m being stalked using spyware—what do I do?

Before a victim of spyware stalking takes any action toward confronting their stalker or trying to stop it from happening, it’s important to consider the risks and proceed carefully. Abusers sometimes escalate their abuses against their partners when confronted, or when they fear they’ll be found out.

Security expert and activist Elle Armageddon wrote for Motherboard last year that decisions made about what to do next are very sensitive:

Having a spyware-infected device while planning to escape an abusive partner, or taking a compromised device while making a getaway, opens people up to more risks than the already extreme threat of being in, and subsequently leaving, an abusive relationship.

Talking to other people about the abuser, making plans to get away, or searching for ways to delete spyware from your phone can all open you up to risk if your phone usage is being monitored. According to Armageddon, carrying on using your devices and living your life as if nothing is amiss may be the safest thing you can do, until you have a plan for escape. Conducting important conversations on a new device, like a prepaid phone, or in-person with confidantes, is recommended.

How do I get stalkerware off my device and prevent it from happening again?

After years of being spied on, it can be difficult to imagine a different way of life.

"I would find myself having conversations with my cell phone in the room that I shouldn't have had with my cell phone in the room," Jessica, a victim of abuser surveillance through stalkerware, told Motherboard last year. "Because you just get lazy, you get tired of being that vigilant and frankly feeling a little paranoid. But at one point I was like, 'I don't care if he listens to every conversation I ever have.”

But there are ways to break out of the surveillance hold someone has on your devices. One option is to wipe your device, and restore it to factory setting.

Keeping your phone up-to-date also helps defend against security threats, including stalkerware. Jailbreaking the phone is often required to install these apps, and newer versions of iOS make that harder to do.

The absence of suspicious apps on your phone doesn’t guarantee that you’re not being surveilled in other ways. Any application that has permission to use your location could be used to track you, such as fitness apps like Strava and running trackers, or even dating apps like Tinder. It’s a good idea to keep your geolocation turned off on your phone as much as possible, in general. To take it a step farther, delete apps like Facebook and Twitter that might show your location in statuses, and use the browser-based versions through a web browser app instead.

Even if you’ve never been a victim of stalkerware surveillance, arming yourself with knowledge on how to spot it—and stop it—could help you or a friend escape a difficult, potentially dangerous situation in the future.

If you are being stalked, you can call the Stalking Resource Center at the National Center for Victims of Crime on 855-484-2846. If you are based in the UK, you can call Paladin on 020 3866 4107.

Photo:

Photo:

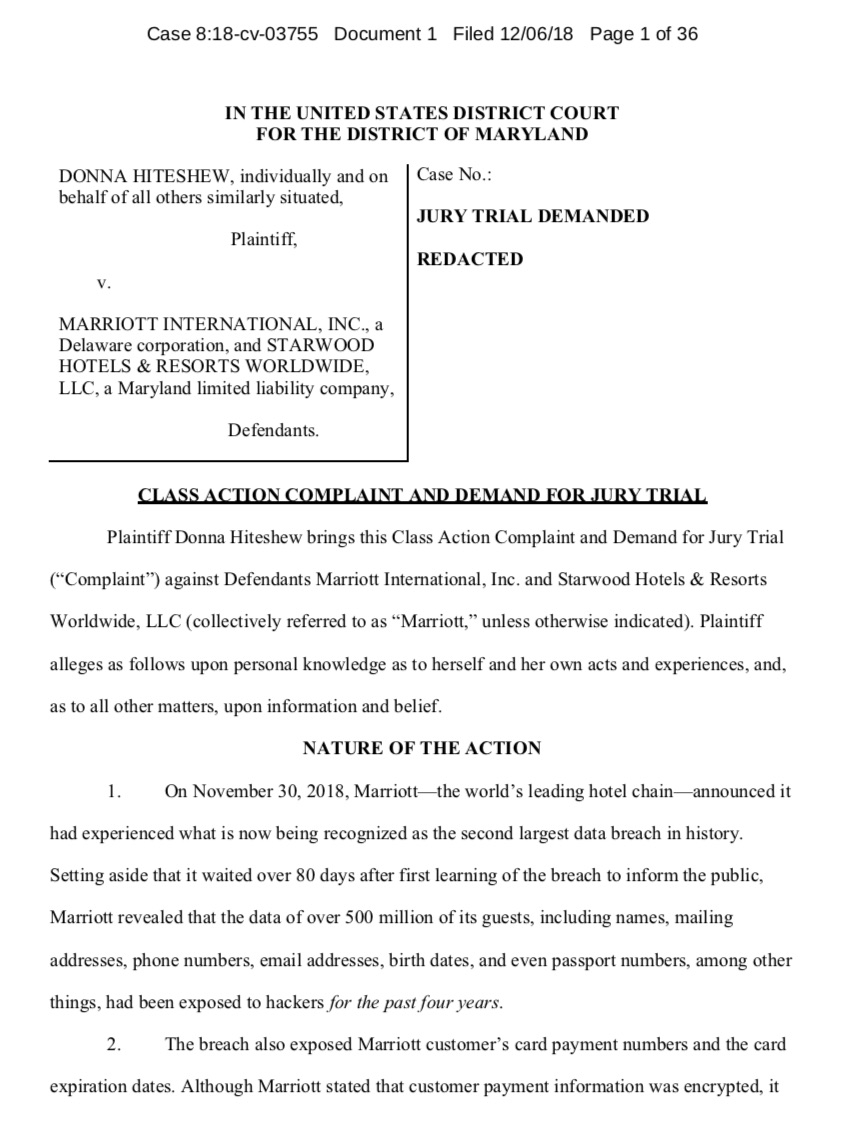

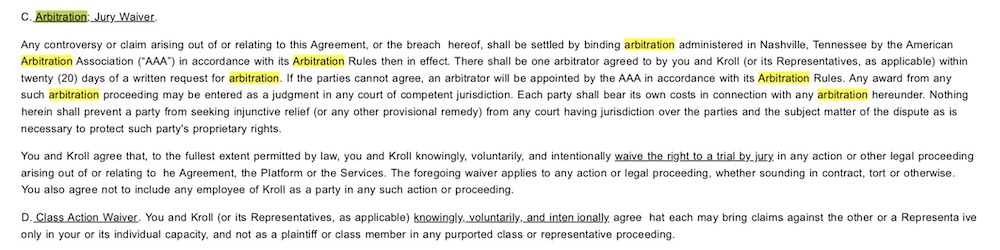

Equifax's 2017 data breach notification to 148 million Americans

Equifax's 2017 data breach notification to 148 million Americans