Breach Notification , Data Breach , Legislation

A Look at Breach Notification Laws Around the World As Europe Preps Mandatory Notifications, What's the Norm Elsewhere?

On the data breach front, a lot has changed since 2003.

See Also: Achieving Advanced Threat Resilience: Best Practices for Protection, Detection and Correction

That's when California began enforcing the world's first data breach notification law, known as S.B. 1386. The law requires organizations in both the public and private sector to notify any California resident if their unencrypted personal information gets exposed, inadvertently or otherwise.

Since then, breach notification laws have continued to spread, although notification is still not mandatory in most countries.

To take stock of the current state of nation's data breach notification requirements, my colleagues at Information Security Media Group and I have explored efforts in four regions:

Europe: The EU's General Data Protection Regulation, which goes into effect in May 2018, includes a number of privacy provisions, including mandatory breach notifications. Some legal experts say the regulation will serve as a model for other countries (see Mandatory Breach Notifications: Europe's Countdown Begins). United States: Some 47 states, three U.S. territories and Washington, D.C., have breach notification laws of varying strength. But efforts to replace them with a single - and more straightforward - federal law have stumbled, in part because previous efforts would have weakened some states' current approaches, Eric Chabrow reports (see Single U.S. Breach Notification Law: Stalled). Australia and New Zealand: Officials in both countries are reviewing mandatory breach notification proposals but have yet to pass any related laws, as Jeremy Kirk reports (see Australia, New Zealand Still Mulling Data Breach Laws). India: Lacking any mechanism for enforcing a data breach notification law, experts say it's unlikely the country will see any related laws anytime soon, Geetha Nandikotkur reports (see Why India is Still Not Ready for Breach, Privacy Laws).Today, nearly 90 countries have data protection laws - or relevant court rulings - on the books, ranging from Angola and Argentina to Venezuela and Zimbabwe, according to the law firm DLA Piper. But many of those countries still don't require breached organizations to notify either authorities or the individuals whose personal information was exposed in the event of a breach.

Data Breach Notification Upsides

Breach notification laws aren't a security panacea, but they do offer upsides:

Consumers get a heads-up that they're at increased risk of identity theft or fraud. Organizations that mishandle personally identifiable information can get named and shamed. Law enforcement agencies can better track attacks and allocate resources to help bust criminals who target, buy or sell PII.But sometimes when PII or emails and passwords get dumped online, the source isn't clear. Notifications are also contingent upon organizations discovering that they've been hacked and then understanding the full extent of the breach. As the 2012 LinkedIn hack demonstrates, the social network failed to spot that more than 160 million user credentials had been compromised until they showed up for sale on an underground forum four years later (see Troy Hunt: The Delicate Balance in Data Breach Reporting).

On the other hand, even some insight into current breaches, on a regional level, can help wake up consumers, legislators and regulators to the full extent of the problem. Until now, for example, only European ISPs and telecommunications firms have been required to report breaches to EU authorities.

"That's one thing that I often smile at, when I hear about Europeans going 'Oh, we must be more secure than U.S. companies because you never hear about data breaches in Europe," Dublin-based information security consultant Brian Honan tells me.

Come 2018, however, all EU organizations will be required to report breaches or risk massive fines. And when the law comes into effect, perceptions will change as the number of notifications rapidly piles up. "Just because you don't hear about it doesn't mean it's not happening," says Honan, who's also an adviser to the EU's law enforcement intelligence agency, Europol.

Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB)

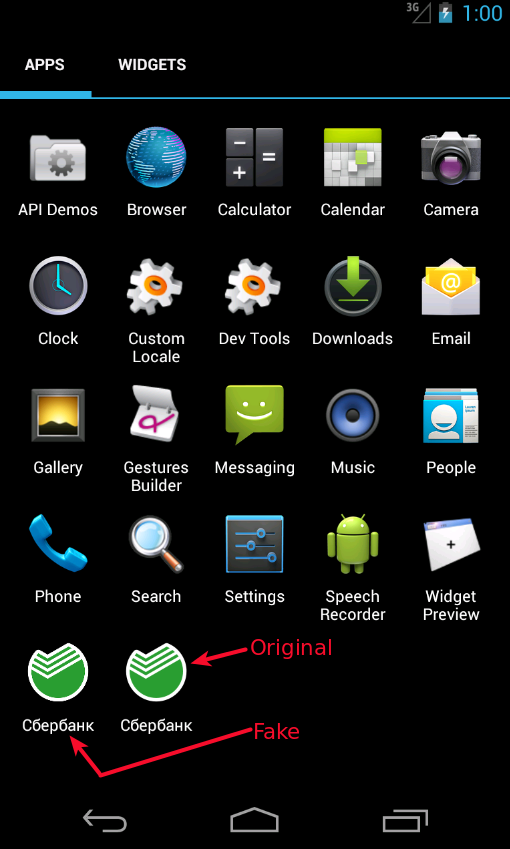

Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) Attackers disguised their malware to look like Sberbank's Android app. (Source: zScaler)

Attackers disguised their malware to look like Sberbank's Android app. (Source: zScaler)

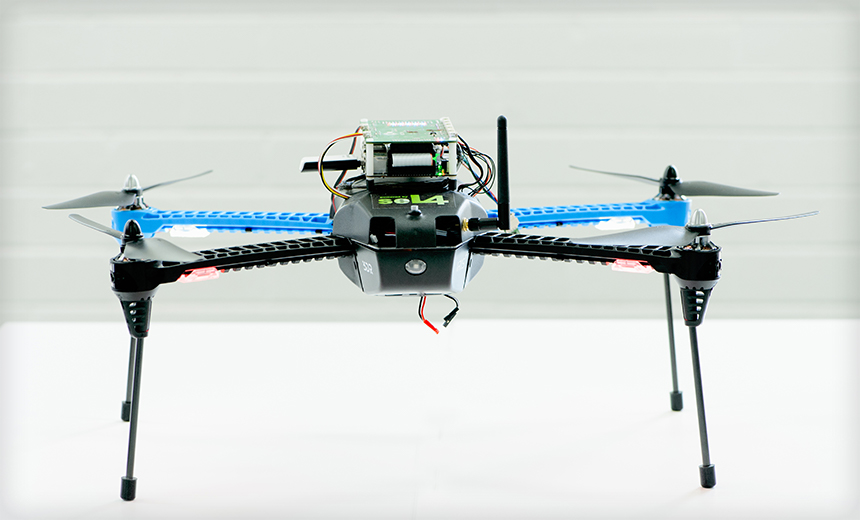

Australia's Data61 research agency has developed a drone that uses an ultra-secure operating system called seL4 that is free of software vulnerabilities, making it resistant to hacking attempts.

Australia's Data61 research agency has developed a drone that uses an ultra-secure operating system called seL4 that is free of software vulnerabilities, making it resistant to hacking attempts.