×Close

Security News

Cybernetics - the science of studying communications and automatic control systems - has emerged as yet another innovative way for practitioners to translate security in context to business (see: Metrics Project May Help CISOs Measure Effectiveness Better).

The approach taken by Sam Lodhi, CISO at the Medicine and Health Products Regulatory Agency in the UK, uses biological cybernetics - or cybernetics applied to the biological context - to help explain the nuances and risk from information security to his business stakeholders, who are professionals in the healthcare and biological sciences fields.

Making a case for security investments can be tricky, he says, and the value of security means different things to different business stakeholders, depending on their perspective and their patience. While no one disputes that security is necessary, many stakeholders are ambivalent about the concepts and do not care for the technical minutiae with which practitioners tend to bombard management (see: Treat Security As a Business Problem First).

"Getting the right engagement from stakeholders is a big challenge for practitioners today," Lodhi says. "A cybernetics-based model can help get the attention security needs by speaking in terms and concepts that business can relate to, using structured, rational analogies from the business's own context, which helps stakeholders understand risk better."

Cybernetics as a science actually provides formal engineering language and diagrammatic approaches to systems analysis, which can be adapted to present information security risk much more credibly, Lodhi says (see: Security: How to Get Management Buy-In).

In this exclusive interview with Information Security Media Group (see player link below image), Lodhi explains how he uses cybernetics to formulate his model to communicate with management and some of the pros and cons of the approach. He also touches upon how this model can be emulated in other verticals. He speaks about:

Applying cybernetics in the information security context; Why the biological cybernetics-based model worked; Broader applicability across verticals.Lodhi is the director at Integrated Business Research Systems, a niche professional services firm specialising in technology, risk and business consulting. He has almost 20 years of experience in enabling security strategy, and has successfully influenced executive committees, sat on group boards to direct security and technology strategy and provided oversight has a non-executive director. He is currently serving as the information security transformation director (CISO) at MHRA - The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, which is an executive agency of the Department of Health in the United Kingdom, responsible for ensuring medicine and medical devices safety.

Anti-Malware , Cybersecurity , Fraud

Report: SWIFT Screwed Up Before Bangladesh Bank Heist, SWIFT Allegedly Overlooked Smaller Banks' Security

SWIFT screwed up.

See Also: How to Illuminate Data Risk to Avoid Financial Shocks

That's the takeaway from a new report into the information security practices of SWIFT, which alleges that the organization overlooked serious concerns relating to smaller banks' security and the risks they posed to the health of its entire network.

More than 11,000 institutions in over 200 countries move money using the messaging system maintained by Brussels-based, bank-owned cooperative SWIFT, formally known as the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication.

The report by the news service Reuters follows hackers' attempt in February to steal $1 billion from the central bank of Bangladesh's account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York by hacking into the bank's Alliance Access software, which was supplied by SWIFT for accessing its central network. With the aid of malware, attackers began issuing fraudulent SWIFT messages and ultimately stole $81 million from the bank.

The theft triggered vigorous finger-pointing between Bangladesh Bank and both SWIFT and the New York Fed over who was responsible for the heist. Bangladesh Bank blamed SWIFT in particular for a botched system upgrade that it claimed had left its systems vulnerable to attackers - a claim that SWIFT denied.

According to the Reuters report, all three were at least partially to blame (see Report: New York Fed Fumbled Cyber-Heist Response). Regardless of who was at fault, the heist created a public relations nightmare for SWIFT, prompting questions over its ability to ensure not just the security but also the authenticity of the money-moving messages it handles, as well as the security-related guidance it issued to customers (see Officials in Several Nations Probe SWIFT Security).

SWIFT didn't immediately respond to a request for comment on the report.

Security Was Overlooked

The new report, based on interviews with more than a dozen senior-level SWIFT managers and board members, details how SWIFT apparently failed to proactively eliminate known vulnerabilities relating to how its smaller banking customers use its messaging terminals. Furthermore, according to the report, in 17 years of annual reports and strategic plans, SWIFT never mentioned security once, except for its 2015 annual report that was issued after the Bangladesh Bank heist, in which it said that it would be helping "our community to strengthen their own infrastructure."

SWIFT's management didn't appear to immediately grasp the severity of the security problem facing the organization in the wake of the Bangladesh Bank hack. In particular, SWIFT first focused on urging banks to review their security policies and procedures. "SWIFT is not, and cannot, be responsible for your decision to select, implement (and maintain) firewalls, nor the proper segregation of your internal networks," read a copy of a letter SWIFT sent to customers, dated May 3 (see SWIFT to Banks: Get Your Security Act Together).

The new report provides substantial evidence that since the 1990s, when many smaller banks in emerging markets began using SWIFT, the organization failed to take into account that their security practices would not be the same as the larger institutions that helped found SWIFT. SWIFT's board continues to be dominated by executives from Western banks such as BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, J.P. Morgan and UBS.

"The board took their eye off the ball," Leonard Schrank, who was CEO of SWIFT from 1992 to 2007, told Reuters. He also suggested that SWIFT's board often lacked a big-picture perspective. "Generally the SWIFT board, with very few exceptions, are back-office payments people, middle to senior management," he said.

Bank Security: Regulators' Responsibility

Former SWIFT board member Arthur Cousins tells Reuters that the organization believed that bank regulators were responsible for ensuring the security of small banks' systems.

SWIFT apparently also failed to track fraud related to its messaging network. Prior to the Bangladesh Bank incident, security experts say that there may have been more than a dozen similar attacks. That included the theft of $12.2 million from Ecuador's Banco del Austro in January 2015, as well as an attempt to steal $1.4 million from Vietnam's TPBank in the fourth quarter of 2015.

SWIFT told me earlier this year that it only learned of the attacks following the Bangladesh Bank heist.

In Progress: Security Overhaul

Since then, however, SWIFT appears to have begun moving quickly to tackle security-related weaknesses in its systems and processes. In the wake of the heists, Gottfried Leibbrandt, SWIFT's CEO since 2012, launched a new customer security program (see SWIFT Promises Security Overhaul, Fraud Detection). He predicted that the Bangladesh Bank heist "will prove to be a watershed event for the banking industry; there will be a before and an after Bangladesh."

In July, together with cybersecurity firms BAE Systems and Fox-IT, SWIFT launched a new digital forensics and customer security intelligence team (see SWIFT to Banks: Who You Gonna Call?).

SWIFT's latest customer security communication, released this week, says that it's highlighting how its Relationship Management Application can be used to filter messages "to ensure that message traffic is only permitted with trusted parties" as well as to revoke communications with any organization, for example, in cases of suspected fraud. SWIFT says it's also made two-factor authentication easier to use in its Alliance Access and Alliance Web Platform products, issuing mandatory updates that better "suit smaller and medium-sized customers and also introduce stronger default password management and enhanced integrity-checking features."

Leibbrandt says funding for the projects, as well as ongoing security improvements, have been earmarked by SWIFT's board. "Hindsight is always a wonderful thing," he tells Reuters. "Sometimes it takes a crisis to change things."

CISO , Governance , Risk Management

4 Questions the Board Must Ask Its CISO Drilling Down on Cybersecurity Plans Vikrant Arora of NYC Health & Hospitals

Vikrant Arora of NYC Health & HospitalsAs CISOs, the most common question we get asked by the board is, "Are we secure?" But there is a fundamental problem with this question.

See Also: API vs. Proxy: Understanding How to Get the Best Protection from Your CASB

In order to explain the problem, I encourage you to ask yourself a similar question - "Are you healthy?" - and see how you respond. Some of you probably started explaining how often you exercise, see a doctor, what you eat and so on.

Others of you would have tried to answer in terms of your family medical history, smoking/drinking habits or medicines/vitamins you take.

For others, the answer may have been "I guess I'm healthy." But no matter how you responded, I doubt the answer was a mere "yes" or "no."

The same problem exists with the "Are we secure?" question for the board. It may elicit information, such as the number of vulnerabilities, intrusion attempts, amount of spam received, devices encrypted, etc. Some of these numbers are in millions and sound impressive, but the answers do not help the board with their responsibility of "making an informed decision."

So, let's take a look at what the board must ask instead.

Question # 1: Is There an Information Security Framework in Place?

The purpose of this question is to ensure that an information security program is based on an industry recognized standard. Use of a framework ensures adequacy of controls, which is more valuable than trying to understand all technical controls, which is just not possible.

A framework helps the board with ensuring effectiveness of controls as well, through the process of internal/external audit. Thus, use of a framework ensures "due diligence" on part of the board while insulating the board from changes in CISOs (personalities), companies or technologies.

In my current role, I am using the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. HIPAA regulations refer to NIST for guidance, so we generally use NIST where applicable. Also, NIST CSF's core security functions - identify, protect, detect, respond and recover - make intuitive sense to non-technical audiences as well. Some other common security frameworks are COBIT and ISO 27K. They all map to one another, so you can use any one and still be able to map to other frameworks.

Question # 2: What is the Scope and Methodology of Risk Assessment?

All security frameworks require a risk assessment to be in place. However, common problems with risk assessments are that they either lack a holistic scope or do not follow a standard methodology. For example, the scope of risk assessment may not include vendors, suppliers or biomedical devices. Results from such a risk assessment cannot offer a 360-degree risk view and may constitute as "willful neglect" on part of the board.

So, the board has to make sure that the scope is holistic. Ensuring a standard risk assessment methodology allows the board to see how the risk is trending on an ongoing basis. And together with a well-defined scope, this will allow the board to properly execute their "advisory and risk oversight" responsibility.

For our purpose, we use the NIST 800-30 Risk Management Guide, which has a nine-step risk assessment methodology. Other security frameworks such as ISO 27K also have corresponding risk assessment methodologies, and I would recommend picking a risk assessment methodology tied to the same framework.

Question # 3: How Do You Measure the Maturity of Processes That Make Up the InfoSec Program?

A CISO is a subject matter expert and should be expected to understand cyber risk better than anyone else in the organization. This question allows a CISO flexibility to highlight key security processes, which may be more relevant to the business, from his or her perspective. It also encourages a CISO to explain an information security program in terms of business-aligned security processes, rather than technology, which can get complex and cause the board to shy away from discussing cybersecurity.

The question also gives CISOs an opportunity to leverage existing business process improvement methodologies, such as Six Sigma and Lean, for process maturity. And there is a good chance that the board is already familiar with such methodologies. CISOs should also be encouraged to include investments made or needed to improve process maturity. This permits the board to see return on security investment, in line with their "fiduciary responsibility."

I have carved my information security program into six high-level security processes: threat management, which includes security monitoring, incident response, vulnerability management and patch management; security operations; security architecture; risk management, which includes risk assessment; policy lifecycle; and security awareness. I also use COBIT 5 for process modelling and maturity assessments.

Question # 4: What Are We Doing to Respond to a Particular Threat That's Making Headlines?

This is an open-ended question that provides an opportunity for both the board and the CISO to discuss threats trending in the media or threats that were previously unknown. For example, this question can facilitate a discussion on advanced persistent threats, including some of the cyberattacks we've been seeing.

The focus on "response" in the question is also an acknowledgement from the board that anyone can be compromised by a determined adversary, and the CISO needs to focus on response and recovery, as much as detection and prevention.

I have used this question to facilitate a discussion on advanced persistent threats, and our company's ability to handle breaches such as those that hit Sony, Target, Anthem and others, or the ransomware attacks that are causing havoc in the healthcare industry.

Ultimately, these four questions are designed to allow a board to actually understand if the organization is secure and also compare their cybersecurity posture with other companies.

Endpoint Security , Mobility , Risk Management

Open Source Software Blocks Malicious Actions, Researchers Say

USB is an old friend, and it's not going away anytime soon. First released in the mid-1990s, the specification eliminated the mess of ports on computers by defining how cameras and hard drives can seamlessly connect to a computer. Even Apple - which has often taking the lead in eliminating ports and drives - has retained a lone USB 3.0 port on its MacBook line of laptops.

See Also: Top Trends in Cybercrime; 411 Million Attacks Detected in Q1 2016

But USB devices, such as flash storage drives, pose a big security risk. Computers blindly trust whatever is on the drive, which is sometimes not what is advertised. That's made flash drives an attractive attack vector because many users blindly trust the devices.

The fear of an attack coming from a USB drive has led to some drastic measures, including filling USB ports with epoxy or using physical locks on ports. But academics say they've developed a defense. They presented a research paper on the project at the Usenix Security Symposium in early August. For the event, they gave away red hats that say: "Make USB Great Again," playing off U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump's campaign theme.

Unleashing Packet-Level Filters

Their software, called USBFILTER, is a packet-level access filter that enforces a tight set of rules for how interfaces on a USB device can interact with the host operating system, says Kevin Butler, associate professor in the computer and information science and engineering group at the University of Florida.

The term interface, in this case, refers to an internal function on a USB device. For example, a USB headset has interfaces for the speaker, the microphone and the volume controls. Operating systems trust interfaces and load the drivers for them automatically. Accordingly, many sneaky USB assaults involve stuffing a secret interface onto the USB drive, then using it as an attack vector.

Figuring out what is a bad interface versus a good one is tough because USB packets are difficult to analyze, Butler says. But the developers behind USBFILTER have engineered it to help assess which packets are coming from which interface. Such knowledge can then be applied to prevent unauthorized interfaces from connecting to the operating system.

The software can also be used to limit what interfaces can do, the developers say. Plug a USB webcam into a USB port on a PC, for example, and USBFILTER can ensure the device only gains access to Skype and can't secretly activate the camera at other times. Or a USB headset with a speaker and a microphone could be restricted to only allow the speaker to interact with an operation system, since microphones also pose a security risk. Or the software can deactivate all interfaces, so that the USB port on a computer can be restricted to only act as a charging port for mobile devices.

"It's a very powerful mechanism that really allows for fine-grained control over any type of data from any type of USB device," Butler claims.

If a USB device other than a real keyboard is programmed to emulate a keyboard, that can also be blocked using the software, the developers say. That could help avoid attacks such as BadUSB, which was described at the Black Hat hacking conference in 2014. In that demonstration, researchers showed that it's possible to rewrite the firmware of a USB device and include malicious functions, such as a secret keyboard, that are undetectable to anti-virus products.

To defend against that, USBFILTER can whitelist the mouse and keyboard of a host machine and drop any other packets representing themselves as those kinds of devices. It still might be possible to try to fool USBFILTER by impersonating those devices with their product and vendor numbers, known as VID/PID, and the serial number, the developers acknowledge. But that would require the attacker to unplug the existing mouse and keyboard and plug the malicious device back in. It's an attack vector that wouldn't work by dropping a malicious USB key in a supermarket parking lot and hoping someone picks it up.

Open Source Approach

USBFILTER is open-source code and has been posted on GitHub. The software has been written for Linux, but Butler says it could be ported to Mac and for Windows.

The real power from USBFILTER will come if it is used throughout an organization and an administrator can centrally control and deploy new rules, the developers say. Related software hasn't been designed yet, but it would mean administrators wouldn't have to worry about what users who access their networks are jamming into USB ports.

"Our eventual hope is that we potentially get this made into a standard part of your operating system," Butler says.

Breach Notification , Breach Preparedness , Breach Response

Should Spy Agencies Alert Political Parties of Cyberattacks? Concerns Raised Over Foreign Impact on America's Election Process

If intelligence or law enforcement agencies know that an organization's information systems are being attacked, when should they alert the victim, if at all? What if the victim is a political party?

U.S. intelligence officials told congressional leaders in a top-secret briefing a year ago that Russian hackers had targeted Democratic Party computers, but the lawmakers were forbidden to tell the target about the breach, according to the news service Reuters.

See Also: Hide & Sneak: Defeat Threat Actors Lurking within Your SSL Traffic

The DNC apparently did not become aware of the breaches until the FBI notified it in April, according to news reports. The FBI publicly revealed the hacks in July, just before the Democratic National Convention, when it announced it was investigating the cyberattacks (see DNC Breach More Severe Than First Believed).

Hackers Influencing Election Process

Emails published by WikiLeaks, ostensibly culled from the breach, showed the DNC leadership favored eventual nominee Hillary Clinton over Sen. Bernie Sanders during the Democratic primary race, with those revelations resulting in the resignation of the DNC's top four officers, including its chairwoman, Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz of Florida.

What makes the Democratic Party breaches worrisome is that the DNC and other political organizations are part of the electoral process that will decide the next president of the United States and Congress. And the failure to promptly alert political organizations that they're under cyberattack could result in the pilfering and publication of sensitive data that could influence the campaign, and potentially, the election.

My last blog, Should Political Parties Be Deemed Critical Infrastructure?, analyzed whether the electoral system, if designated by the federal government as critical infrastructure that needs additional cyber protections, should include just the voting infrastructure or be expanded to other organizations, including political parties, that have an impact on elections.

Russian Interference?

This is especially relevant because the Russian government is believed to be behind the Democratic Party hacks. Do hacks by a foreign nation interfere with the American electoral process if leaks of information from political party computers are made public? Of course, they do.

And it's not just the release of damning information that could help sway an election; it's also whether hackers tampered with leaked information. "You may have material that's 95 percent authentic, but 5 percent is modified, and you'll never actually be able to prove a negative - that you never wrote what's in that material," CrowdStrike Co-founder Dmitri Alperovitch told the news site Politico. "Even if you released the original email, how will you prove that it's not doctored? It's sort of damned if you do, damned if you don't."

Still, under certain circumstances, intelligence agencies and law enforcement want to keep a hack hush-hush, not even alerting the victim, "because they don't want to alert the attacker so they can build a criminal case against them or gain a better understanding of the adversary that could produce intelligence and/or create better defenses," says Stewart Baker, a former DHS assistant secretary for policy.

Former FBI Special Agent John McClurg explains how a tip from law enforcement of a hack helped protect an information system.

But in some circumstances, victims can be alerted without jeopardizing intelligence services getting the goods on the hackers, as John McClurg, Cylance vice president and former FBI special agent, said happened when he served as chief security officer at Honeywell International.

Seeking Balance

In the electoral process, should the needs of the intelligence community and law enforcement take precedence over preserving the integrity of the voting system?

There's no simple answer, and some experts contend each instance of a cyberattack must be judged on its own merits. "Sorry, there is no simple algorithm that we can use to get to the right answer," says Robert Bigman, former CISO at the CIA.

Bigman says the intelligence community acted correctly by not notifying the DNC of the alleged Russian intrusion into their systems last year. He suggests that by not alerting the DNC - and perhaps tipping off the hackers - CrowdStrike forensic experts contracted by party leaders were able to identify the malware code used in the breaches, which has been tied to previous Russian hacks.

Blown Sources?

Stewart Baker, a former DHS assistant secretary for policy, points out that law enforcement and intelligence agencies don't always notify victims when they detect an attack so that they can "keep secret any [breach investigation] sources and methods that could be put at risk. ... As the risk of harm to the victims becomes more imminent, the balance shifts, and more creativity might be devoted to finding a way to provide notice without risking sources. In the case of hacks aimed at the Democratic campaign, it's worth noting that the parties were also hacked in 2008 and 2012 by nation-states, so only someone very naive would ignore the risk in 2016. One question the government may have asked is whether telling the targets about the risk would actually lead them to protect themselves effectively. If not, you've blown a source for nothing."

But alerting an organization about an ongoing cyberattack could raise awareness of vulnerabilities that could be addressed. Yet, knowing a hack is occurring doesn't always necessarily mean the information garnered can be used to mitigate the breach.

"Many indications and warnings are not particularly actionable," says Martin Libicki, a cyber policy expert at the think tank The Rand Corp. "The intelligence community hasn't publicly revealed what it knows and how it gained that knowledge about the attack on Democratic Party computers, making it hard to evaluate whether earlier disclosure would have made a difference."

Nonetheless, political institutions play a key role in our electoral process. If these groups are hacked, intelligence service should err on the side of notification.

Anti-Malware , Fraud , Risk Management

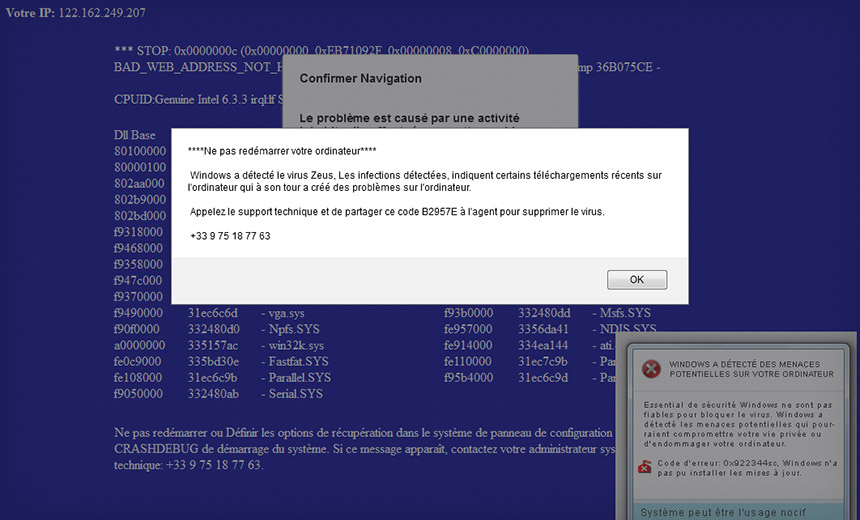

Researcher Unleashes Ransomware on Tech-Support Scammers Fun Factor Aside, 'Hacking Back' Carries Legal Risks This scam tech-support site claimed a visitor's PC was infected with Zeus malware.

This scam tech-support site claimed a visitor's PC was infected with Zeus malware.Who doesn't hate tech-support scammers?

See Also: Detecting Insider Threats Through Machine Learning

Thanks to French security researcher and malware analyst Ivan Kwiatkowski, however, we can share in some tech-support scammer one-upmanship.

After Kwiatkowski's parents stumbled onto a tech-support scam website, he says that he ultimately retaliated by tricking one of the site's supposed tech-support agents into executing a Locky ransomware installer on his system.

Kwiatkowski says in a blog post that his parents, in France, recently got a new computer and were online for all of 30 minutes before stumbling across a site that warned them that their PC was infected with the Zeus virus that Windows couldn't fix. The site advised them to immediately contact a listed telephone number, which began with a French country code. Instead, they phoned their son, who warned them away.

My parents have had a new computer for 30 minutes and have already stumbled upon an online scam. I can't even. https://t.co/9eMRpf3y6z

The Usual Smoke and Mirrors

Kwiatkowski then opted to fire up a Windows XP virtual machine and reached out to the "tech support" team, getting a woman named Patricia on the phone who instructed him to install a remote-support client that she then used to access his system. Without recognizing the VM environment, and while sticking closely to a French-language script, he says Patricia then typed in a number of commands to make it appear as if his system was infected with a virus.

Kwiatkowski says he played along, capturing screenshots along the way. After claiming that his 15 minutes of free tech support time were up, Patricia said he needed to buy an anti-virus program priced at $189.90. "Before I have the opportunity to get my credit card, she goes back to the terminal, runs netstat and tells me that there's someone connected to my machine at this very moment."

Kwiatkowski says he replied: "Isn't that you? ... This says it's someone from Delhi."

Eventually, Kwiatkowski begged off, but he called back again 30 minutes later after realizing that some of his screenshots didn't work.

This time, his call was answered by "Dileep," who said he needed a €299.99 ($338) "tech protection subscription."

"In the meantime, I hear other operators in the background repeating credit card numbers and CVVs aloud," Kwiatkowski says. At that point, he opted to retrieve a JavaScript Locky installer from his email junk folder, which he uploaded via the remote-support client, telling the agent: "I took a photo of my credit card, why don't you input the numbers yourself?"

Kwiatkowski says he hopes, but doesn't know for sure, that the scammer's system - and every other system to which it connected via the local area network - was then forcibly encrypted by the ransomware.

Don't Try This at Home

Kwiatkowski doesn't advocate this course of action for other potential tech-support victims. But he does urge everyone to waste scammers' time by keeping them engaged in meaningless phone chatter for 15 minutes, thus taking a bite out of their profits.

To be clear, phoning scammers is one thing. But security experts have long warned that individuals - or nation-states - that attempt to "hack back" may face serious repercussions. "There's a lot of talk around hacking back - and while it may be very tempting, I think it should be avoided to stay on the right side of the law," University of Surrey computer science professor Alan Woodward tells the BBC.

"But wasting their time on the phone I have no problem with," adds Woodward, who's also a cybersecurity adviser to the EU's law enforcement intelligence agency, Europol. "I even do that myself!"

Support for Tech Support Scam Victims

Kwiatkowski's story is a reminder that while fake tech-support gangs' claims might seem outlandish, less technically savvy PC users sometimes fall for them.

@nevali a friend had someone allegedly from Microsoft threaten to blow up his computer.

Based on stories I've written about fake tech-support gangs, many victims have reached out, asking me if they've been scammed and what they can do about it. The short answer: File a fraud report with your credit card company. Also report the attempted fraud to relevant authorities, such as the FBI's Internet Complaint Center or to the U.K.'s ActionFraud.

Doing so helps authorities track these scams and hopefully disrupt them - no ransomware "hacking back" required.

Police have arrested an employee of U.K.-based accountancy and business software developer Sage Group after a data breach. Meanwhile, a report has emerged that some customers are using its software in an unsecured manner.

See Also: How to Mitigate Credential Theft by Securing Active Directory

On Aug. 17, City of London police arrested a Sage insider, following the company warning via its website on Aug. 14 that 200 to 300 U.K. businesses may have been affected by a data breach related to the use of an insider's login credentials.

"The City of London Police arrested a 32 year-old woman on suspicion of conspiracy to defraud at Heathrow airport," a spokesman tells Information Security Media Group. "The woman was arrested in connection with an alleged fraud against the company Sage. She has since been bailed. The woman is a current employee of Sage."

Sage declined to comment on that report, citing the ongoing investigation.

A 32 y/o woman has been arrested in relation to the ongoing fraud investigation from the business firm Sage

Sage says its customers include 6.2 million businesses in 23 countries; it has 13,000 employees. The company is the only technology stock still listed on the FTSE 100 - the 100 largest companies listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Breach Tied to Insider Credential

The data breach stemmed from inappropriate use of a legitimate access credential, Sage reports. "We believe there has been some unauthorized access using an internal login to the data of a small number of our U.K. customers, so we are working closely with the authorities to investigate the situation," Sage says in a notice published on its website. "Our customers are always our first priority, so we are communicating directly with those who may be affected and giving guidance on measures they can take to protect their security." The company also published a toll-free number that all customers can call to receive further information.

Sage says it's also informed Britain's privacy watchdog, the Information Commissioner's Office, about the breach.

"We're aware of the reported incident involving Sage UK, and are making enquiries," an ICO spokeswoman tells ISMG. "The law requires organizations to have appropriate measures in place to keep people's personal data secure. Where there's a suggestion that hasn't happened, the ICO can investigate, and enforce if necessary."

Shodan Unearths Unprotected Servers

Separately, serial bug spotter Chris Vickery says that on Aug. 11, he found that more than 20 organizations were using on-premise Sage X3 servers with poorly configured versions of the MongoDB open source database, raising serious security concerns. Vickery said he spotted the databases via Shodan - a search engine for internet-connected devices and services. The servers are meant to be used by companies with 200 or more employees, he points out.

"So finding more than 20 of them completely exposed to the public internet, with no username or password required for access, was a little unnerving," Vickery says via an Aug. 18 blog post on the site of controversial anti-virus software developer MacKeeper (see MacKeeper Hid Product Update Error). MacKeeper, which last year settled a class-action lawsuit alleging deceptive advertising and false claims, hired Vickery after he warned that the company had inadvertently exposed millions of customers' personal details online, which it then fixed (see MacKeeper: 13M Customers' Details Exposed).

In the case of the Sage servers, Vickery says that some "contained massive amounts of company records in the form of PDFs, DOCs, and XLS spreadsheets," and that he initially warned Sage, believing that it controlled the servers directly. "High-level Sage staff members sent a response back within hours - rather impressive when considering the U.K. time zone difference," he says. "We engaged in a telephone conversation shortly thereafter. The Sage representatives were very clear that while they claim Sage is not at fault for these breaches, Sage is extremely concerned with any situation involving their software being implemented insecurely by clients."

Vickery says that he supplied IP addresses for vulnerable installations to Sage, and that the company has begun directly notifying affected customers. But he warned that the affected companies' information may have already been accessed by other parties.

"I've found logs indicating that I am not the first person to discover these exposed servers," he says. Sage declined to comment on that assertion.

Vickery warns all Sage X3 software users to ensure that they lock down the software. "If you are a large Sage client, make sure that your software installations are behind a firewall or, at the very least, you have some sort of access restrictions in place," he says. "Most companies do, but I know of at least 20 that did not."